UK dietary guidelines are designed to promote healthy eating by providing accessible advice to the public. But what we eat doesn’t only impact on our individual health, it also has much larger impacts on the health of our planet – upon which human health is reliant. At present, we are producing and consuming food in ways that will ultimately limit our ability to feed future generations equitably. There is growing interest in integrating elements of sustainability into healthy eating guidance, and several countries have produced guidelines that explicitly align health and environmental sustainability into dietary recommendations. While the UK’s 2016 updated dietary guidelines have also taken some steps to incorporate sustainability, much of the messaging is not explicit. So how do the UK guidelines compare?

What is the Eatwell Guide?

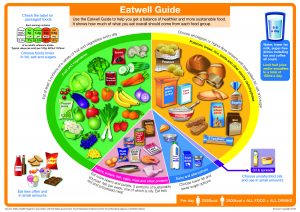

The Eatwell Guide is the UK’s official food guide to healthy diets, which breaks food down into five groups (fruit and vegetables, starchy carbohydrates, dairy and alternatives, non-dairy high protein foods, and oils and spreads). It advises what proportion of our diet these food groups should make up, and highlights some of the “healthier” choices within these groups. While the Eatwell Guide is designed to be suitable for use by the general public, it also informs and influences practices more widely such as in schools and hospitals.

Why is sustainability relevant to the Eatwell Guide?

Although given little consideration during the United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP21) climate change talks in Paris, the global food system has a significant environmental impact. Food production and distribution is the leading cause of global deforestation, land use change and biodiversity loss, contributes almost a quarter of human produced green house gas (GHG) emissions (a leading cause of climate change), and is accountable for more than two thirds of all water used by humans.

While both crop and livestock production impact negatively on the environment, rearing animals for food has a much larger environmental footprint. Raising livestock for meat, dairy and eggs is responsible for around 14.5% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Of this, 39% can be attributed solely to methane production from cattle and sheep. Livestock production also uses 70% of agricultural land – a third of which is used in production of feed crops for livestock.

Thus, which foods we choose to eat can have significant impacts on human health and environmental sustainability at a global level, and we cannot ignore the role of dietary guidance in promoting both human and planetary health.

How does the UK compare with other guidelines?

Several countries around the world have begun to incorporate elements of sustainability into their dietary guidelines, and this blog is focused on comparing the UK to those addressing sustainability elsewhere in Europe. Table 1 compares advice on the intakes of meat, dairy, eggs, fish, fruit and vegetables, pulses and legumes, and carbohydrates and fibre taken from national dietary guidelines of Sweden, Holland, Germany and the UK.

Overall, the Eatwell Guide does provide some limited sustainability messaging, and a review by the Carbon Trust indicates that the guidelines are measurably more sustainable than current diets. However, in terms of specific recommendations for different foods, the UK guidelines are lacking – opting for the terms ‘some’, ‘more’ and ‘less’, rather than quantified amounts. For example, while the UK guidance does provide an overall message to consume less meat, it does not provide specific guidance around consumption of different meat or dairy products (except for limiting red and processed meat to 70 grams per day). Sweden and Holland both recommend limiting overall meat consumption to 500 grams per week, which is just over half the current average UK male consumption (900 grams), and less than the average female consumption (620 grams). Sweden, Holland and Germany also provide quantified guidance on dairy products.

Although Sweden, Holland and Germany have primarily based their meat and dairy recommendations on health needs rather than sustainability, overall their guidelines go further than the UK in highlighting the environmental impact of meat consumption. Whilst Holland and Germany only focus on red meat in this context, Sweden emphasises the environmental benefits of eating less meat and dairy overall, and consuming more plant-based foods. Sweden and Germany also recommend choosing seasonal fruit and vegetables.

Sweden most effectively threads sustainability throughout their guidelines, explicitly linking health and environmental issues to every food group (including dairy), and even highlighting which plant-based foods are to be preferred (for example, root vegetables over salad greens due to their robustness and lower environmental impact). All four countries draw the links between sustainability and fish consumption, and Holland has even reduced recommended intake to once per week, specifically to address sustainability concerns. Sweden and Holland also incorporate animal welfare considerations into their guidelines, while Germany and the UK do not.

Challenges and opportunities for incorporating sustainability

One challenge to embedding sustainability into dietary guidelines is that no metrics yet exist which define what a sustainable diet would look like, making it difficult to provide detailed recommendations around meat intake. Nevertheless, there is strong evidence to show that an overall reduction in meat consumption would be better for the environment, and much work has sought to define the elements of a sustainable diet. For example, the Food Climate Research Network (FCRN) is doing a great deal of work in this area. WWF’s Livewell 2020 Plate provides a UK-based example of a diet that would deliver on health and sustainability (carbon) outcomes, and recommends that meat, dairy and eggs make up 4%, 15% and 1% of the diet respectively. This guidance is currently being updated to also include the water and land use impacts of different foods. Recently, the Food and Agriculture Organization and FCRN reviewed national dietary guidelines worldwide, and their report provides comprehensive recommendations for both the development process and the content of food-based guidelines. Furthermore, other EU countries such as France, are updating their guidelines to include advice to eat less meat and more plant proteins, such as pulses, although they stop short of making an explicit link to sustainability.

Public Health England have taken a very important first step in including limited sustainability messaging in the updated Eatwell Guide, but there is still some way to go to truly embed this within dietary guidelines, and have a real effect on food consumption. Whilst other countries in Europe have been more explicit about sustainability, their guidelines are still primarily led by health, and the UK needs not only to include more explicit messaging, but also to more widely consider both health and sustainability together. These are only the first steps in shifting eating patterns to those that are more sustainable, but they are vital ones.