By Medact & Nags Head Tenants Association with support from Disability Rights UK

Authors: Hil Aked, Calum Barnes, Isobel Braithwaite, Leckhna Chajed, Pip Eldridge, Michael Erhardt, Alastair Howard, Asif Khapedi, May Mardam Bey, Sabrina Monteregge, Anna Ogier, Mariam Omar, Freddie Weyman, India Whalley

Citation: Aked, H. et al. (2025) Nags Head Estate: Tenants’ Experiences of Unhealthy Homes, London: Medact.

Contents

Foreword by Nags Head Tenants Association

4. Issue reporting and resolution

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Appendix I: Photos of Nags Head housing issues

Appendix II: Nags Head in the Media

Foreword by Nags Head Tenants Association

The Nags Head Tenants Association formed in 2020, just prior to the UK going into a series of lockdowns. While our initial activities focussed on providing mutual aid during the pandemic, it was not long before the group became focused on tackling the significant neglect experienced by tenants and calling for estate improvement.

Built in the 1930s, the Nags Head estate is located next to the affluent Columbia Road Flower Market and situated near the periphery of the City of London. It is not lost on us that the appalling conditions on the estate exist in close proximity to extraordinary wealth in one of the most sought-after property locations in east London. Across the Nags Head Estate we identified long-standing disrepair and frustration with Peabody with regards to how repairs were dealt with, or in many cases left unfixed. Through our tenant assemblies and meetings we began to realise that similar issues of damp, mould, pests and disrepair were systemic across the estate, causing tenants illness, stress and negatively impacting on their wellbeing. Our efforts to collate and communicate these issues to Peabody were met with the mantra “There is no money for estate improvement”. This was often relayed with a baffling synopsis of the Peabody budgetary system and a hefty dose of tenant-blaming. Inevitably, we became fed up with this abdication of responsibility and the manufactured incompetence that trickles down from the Peabody hierarchy to the overstretched staff tasked with dealing with issues. So, in 2023, we decided to change tactics.

In 2023, we made contact with Medact and with this organisation we began a campaign aimed at holding Peabody to account for the structural issues causing damp and mould, alongside demanding that the disrepair on the estate caused by neglect be remedied. With Medact’s support, we engaged tenants through door-knocking and holding tenant assemblies, alongside connecting to organisations such as London Renters Union and Disability Rights UK. This led to the establishment of a group legal claim and participation in several high-profile media exposés. Throughout this process we uncovered the devastating human cost of Peabody’s failure in its duties as landlord. This includes significant and severe respiratory illness exacerbated by black mould and a serious dereliction of care towards disabled tenants. We also laid bare the widespread denigration of mental and physical wellbeing stemming from the appalling condition of the housing on the estate and the futility of trying to navigate the many outsourced companies that comprise Peabody’s repairs system. Equally notable were the many tenants suffering from the shame and stigma of living in unfit conditions while undertaking excessive domestic labour daily to render their properties safe for their families. Significantly, the investigations have evidenced that it is estate-wide structural faults and neglect that are the cause of damp, mould and disrepair. This includes lack of adequate insulation alongside a failure to maintain the infrastructure of the estate on a cyclical basis and an unfit system for dealing with refuse.

Through our campaign we have been able to upend the default position of tenant blaming and direct the responsibility where it belongs: Peabody’s organisational dysfunction and consistent outsourcing of its services. The neglect on our estate is not unrelated to Peabody’s unwieldy expansion towards becoming one of the largest landlords in the UK. Peabody’s focus on the acquisition of other housing associations and the building of shared ownership properties has left its existing stock in a spiral of decline. Our public calling out of Peabody’s failures has led to a budget finally being allocated towards estate improvement and investment works, and an in-sourced repair team, along with improved efforts at tenant engagement, including co-design with tenants which is in its infancy. Whilst the efficacy of these works remains to be seen, we hope to move beyond the quick-fix sticking of plasters on problems towards more long-term cures. Of course, it is also a real shame that we had to air Peabody’s failures in public to get this far. Had there been genuine efforts to address tenants’ concerns and proper investment in maintaining the estate prior to this, such action would not have been necessary. This raises concerns around the conditions on estates where tenants are not organised.

Our collective struggle has not been without joy. It has strengthened our community and built solidarity across our estate. We are incredibly proud of all the tenants and block reps who, despite adversity, have stood up, spoken out and fought for our community together. As a community we are strong, organised and highly co-operative. Neighbourly care and kindness are the bedrock of our community. We look out for each other and also have fantastic community gatherings, which always have the most diverse array of delicious cultural dishes on the sharing table. Communities like ours represent the best of London and we deserve better. We caption our newsletters with the adage ‘you don’t get anywhere if you don’t nag’ and Nags Head tenants will keep on nagging until we have safe, warm, secure and genuinely affordable homes across the estate – as is our right.

Executive summary

- This report presents research into conditions on the Nags Head estate, east London, which is managed by Peabody – one of the largest housing associations in Britain.

- It is based on housing and health surveys of a quarter of the estate’s social housing and key worker tenants, supplemented by interviews and direct observations.

- While highly specific, it provides a window into the wider housing and health crisis, because case studies like it – in which low-income and often racialised communities are forced to live in unfit housing – are replicated across the country.

Housing conditions

- Overcrowding – itself a health issue and a risk factor for others – is prevalent, with the average Nags Head household containing 3.6 people but just 2.3 bedrooms.

- Mould and damp are major problems with an alarming 95% of households reporting visible mould and 83% the presence of damp.

- More than two thirds (68%) of households on the estate reported leaks or plumbing problems and more than one third (36%) reported disrepair, sometimes leading to injuries.

- We also received numerous anecdotal reports of pest infestations which were not addressed adequately.

Health impacts

- In 57% of Nags Head households, at least one person lives with chronic health conditions.

- A worrying 86% of households reported new symptoms or injuries since moving into their properties – especially mental health and sleep-related issues.

- Shockingly, almost three in every five households (58%) reported at least one member developing a respiratory condition since moving to Nags Head, likely related to the widespread mould and damp on the estate.

- More than a quarter (27%) of households reported at least one disabled member; of these, more than two thirds (67%) believed their living situation was making their condition worse.

- The majority (65%) of disabled tenants had informed Peabody about their disability and requested adjustments or adaptations to their property but most reported that their accessibility needs were not adequately met.

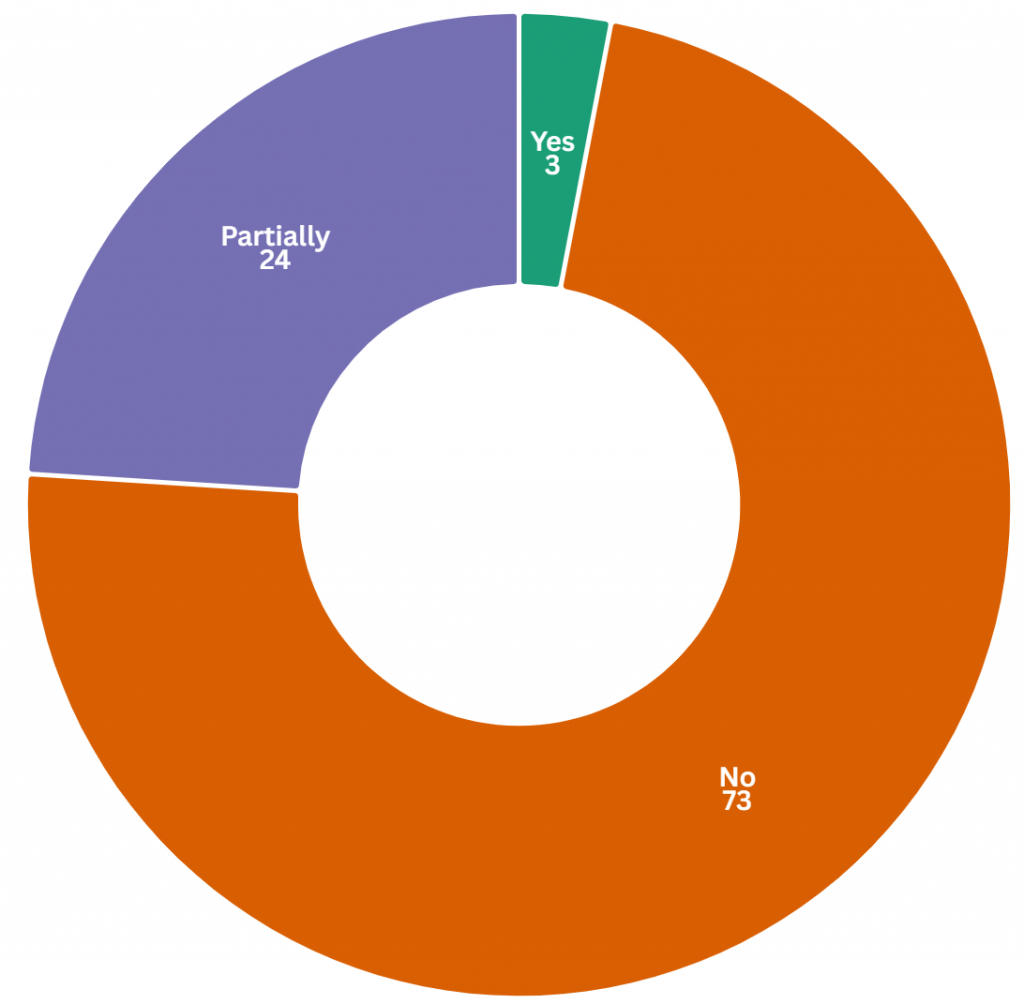

- In general, when issues were raised, repairs took unacceptably long and just 3% of tenants were satisfied, while almost three quarters (73%) said issues remained unresolved – a status quo which compounded the mental health strain of the neglect.

Recommendations

To Peabody:

- Ensure tenants have safe, warm homes through an immediate retrofitting programme involving full consultation with residents, and simultaneously improve ventilation where needed to prevent condensation buildup and mould-growth.

- Adequately maintain the estate through prompt on-site repairs, improved waste management and pest control, more caretaking capacity, and regular upkeep of roofs, gutters, drains, and communal spaces.

- Support disabled tenants to access occupational therapy, council needs assessments and the adjustments and adaptations they need, while training staff in the social model of disability.

To local authorities:

- Ensure housing association tenants know of their right to escalate issues to the council when unaddressed by the landlord, and make greater use of environmental health teams’ enforcement powers to intervene in housing situations which risk tenants’ health.

To NHS bodies:

- Ensure health workers are equipped to signpost tenants to information and resources, make referrals, and escalate issues when they become aware of housing issues causing or exacerbating health conditions that are not being adequately addressed.

1. Introduction

Housing as health

“Home is somewhere that is safe and warm, somewhere that looks nice and that is spacious enough for everyone, and somewhere for you to feel at ease at the end of the day”

– Resident from Horatio House, Nags Head estate

Our collective health is fundamentally shaped by the social and material conditions we are born into and those in which we grow, live, work and age. The so-called ‘social determinants of health’ are underpinned by political and economic systems that dictate how power, wealth and resources are distributed. Together, these factors create unequal exposure to health risks and disease, resulting in stark health inequities.

Housing quality, security, affordability and accessibility are key structural drivers of health. For some, the bricks and mortar of our homes provide a foundation for our health and wellbeing, whilst financial affordability provides the stability essential for people and communities to thrive. For others, however, instead of places of safety and growth, our homes have become hotbeds of illness.[1]

Across the UK, millions are living in cold, damp and mouldy housing.[2] These conditions, compounded by issues like fuel poverty, disproportionately affect those with the least socio-economic and political power – and have a myriad of negative impacts on physical and mental health.[3] As such, the UK housing system cements the twin injustices of poverty and health inequity across generations.

Damp and cold homes increase the risk of respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease and overall mortality rates. The longer individuals are exposed to such environments, the greater risk of harm to their physical health.[4] Unaffordable, insecure and overcrowded housing poses mental health hazards too. Inevitably, stress and anxiety are associated with struggling to pay bills, falling into rent arrears, lack of privacy, or being forced to choose between heating one’s home or eating decent meals. Furthermore, the fear of eviction or the inability to leave poor-quality housing can create a diminished sense of control and agency which may contribute to depression and other mental health conditions.

The significant physical and mental health impacts of poor housing go beyond individuals. The whole of society ultimately bears a cost, through health services and social care. According to recent research, poor housing costs the NHS an estimated £1.4 billion every year.[5]

Nags Head estate and tenants association

The Nags Head estate is situated in Tower Hamlets, east London. Built between 1933 and 1947 by the Nags Head Housing Society, the estate was bought by Peabody, one of the largest housing associations in the UK, in 1956. It consists of seven apartment blocks, one of which (Shipton House) mainly houses residents in supported accommodation. The remaining six blocks – Haig House (25 units), Maude House: (27 units), Jellicoe House (15 units), Sturdee House (39 units), Cadell House (14 units) and Horatio House (27 units) – house social and intermediate rent tenants.

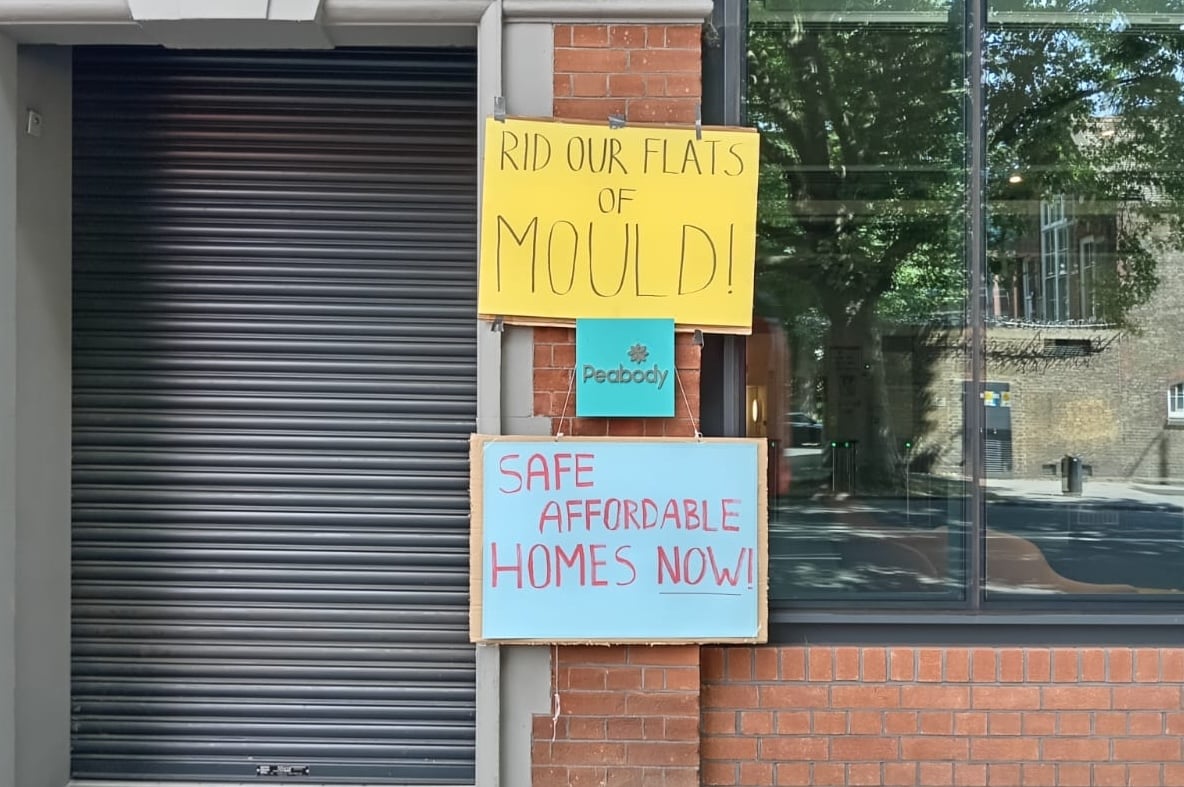

Residents of the estate formed the Nags Head Tenants Association due to prolonged poor housing conditions – including damp, mould, pest infestations and structural disrepair – which they had been reporting to their landlord, Peabody Trust, for years, with little action in response. The group united residents, facilitated communication, and provided a framework for coordinated action to demand better living conditions. During the COVID-19 lockdown of 2020, tenants began collectively organising to force Peabody to address these issues. Over the last five years, they have held protests outside Peabody’s headquarters to highlight the neglect and demand immediate repairs, and they have spoken out in the media (see Appendix II).

Since 2023, the tenants association has been collaborating with organisations like Medact and the London Renters Union, who have provided support in raising awareness and pursuing legal action. While this eventually prompted some action from Peabody, residents report that many issues remain unresolved and continue to advocate for comprehensive repairs and accountability. The tenants’ collective action underscores the importance of community organising for holding housing associations to account in the struggle for safe, healthy living environments, both locally and nationwide.

Methods

Medact’s Economic Justice group – a collective of health workers organising and campaigning around issues of economic inequality – was first contacted by the Nags Head Tenants Association in 2023, following numerous reports of respiratory problems amongst residents thought to be associated with widespread mould and damp on the estate. Following an initial meeting with the tenants association, Medact proposed conducting surveys and interviews in order to systematically collect information on housing and health conditions across the estate.

The aim of the survey was to better understand how residents’ housing might be impacting their health. In addition, by documenting their experiences, tenants hoped to provide an evidence base to support their campaigning work to improve their living conditions – work which Medact has been proud to actively support throughout. This approach is consistent with our research policy which explains why rigorous research does not need to perform neutrality,[6] and with the Human Impact Partners Research Code of Ethics which asserts that research should be “beneficial to communities”, “collaborative and in close communication with partners”, and should “support partners’ work to change policy and improve living conditions”.[7]

Medact members surveyed households in the six blocks of the Nags Head estate housing social and key worker tenants. They did so accompanied by tenants, in an effort to minimise power imbalances and ensure that research was conducted with rather than ‘on’ or ‘about’ residents. Participants were recruited through a combination of door-knocking and attending community meetings. Members of Disability Rights UK, advocating on behalf of disabled tenants, also provided invaluable support.

The survey explored tenants’ experiences of housing and health, and the potential connections between them. It consisted of two parts. Part 1 documented information about their homes, including the number of people in each household, the presence of mould and damp, and other issues such as disrepair, accessibility, and fire safety. Households were also asked if issues had been reported to the landlord and, if so, whether they had been resolved. Part 2 asked questions about households’ self-reported health issues, both physical and mental, including pre-existing and newer conditions.

In total, 37 households completed surveys about their housing, on behalf of a total of 140 residents, representing 25% of the social tenancy households on the estate. Health data was collected from a slightly smaller sample of 35 households due to a small number either declining to provide this information or insufficiently completing the survey.

In addition, four interviews were conducted to gather more in-depth qualitative data for case studies about some of the most notable issues. Some preferred for their testimonies to appear under a pseudonym.

Finally, Medact members also collected data through direct observation, visiting dozens of properties across the estate and recording examples of disrepair, mould and damp that they witnessed first-hand.

2. Housing conditions

“Who would take on a property if your landlord said, ‘oh well, in order to live here, what you have to do is mould wash at least once a week and dehumidify all the rooms’… nobody would sign up to a rental property like that”

– Kevin Biderman, resident at Jellicoe House, Nags Head Estate

Overcrowding

Household overcrowding is a growing problem in England. In London, as a result of a severe shortage of social housing and exorbitant private rental costs, there are an estimated 149,000 overcrowded homes. In the borough of Tower Hamlets alone, where over 23,000 residents are currently on housing waiting lists, 14,000 residents are living in acutely overcrowded homes.[8] Consistent with this, survey results showed that overcrowding is a prevalent issue on the Nags Head estate.

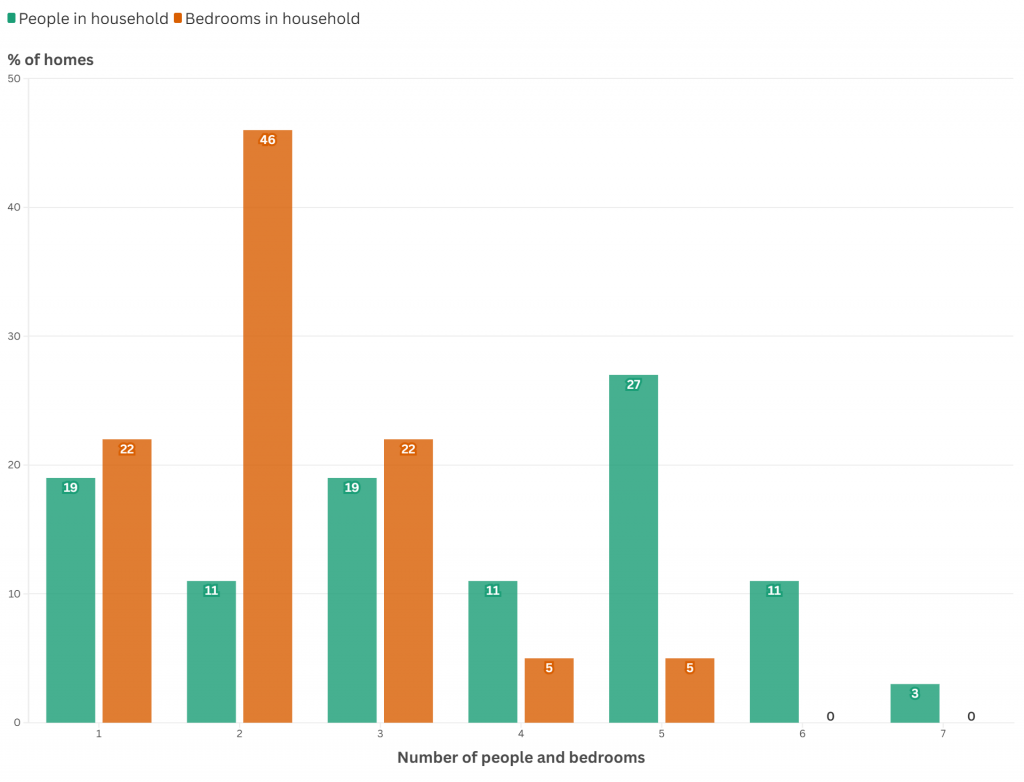

As Figure 1 illustrates, results showed that while 40% of households surveyed consisted of five or more people, only 32% of flats had three or more bedrooms, compared to 69% of flats with two bedrooms or fewer. The average number of people in a household was 3.6 but the average number of rooms in a property was 2.3. Overcrowding often coincides with and contributes to other housing problems, such as damp and mould, and it is a risk factor for many health outcomes including infections, injuries and poor mental health.[9]

Mould and damp

Dampness – patches of moisture or condensation on walls or ceilings – refers to materials and structures in a building that contain or absorb excessive moisture. It can occur due to poor building design, structural deficiencies, or poor ventilation and insulation, all of which may allow moisture to enter buildings from the outside via the walls or roof (penetrating damp), through the floor (rising damp), or as a result of humid indoor air condensing on internal surfaces (condensation damp).

Damp and excessive humidity can in turn lead to mould growth, which can cause allergic reactions, the development and worsening of asthma, respiratory infections, coughs, wheezing and shortness of breath.[10] An estimated 31,000 babies and toddlers are admitted to hospitals annually with lung conditions caused or exacerbated by cold, damp and mould.[11]

Helena and Kevin’s story

We moved to the Nags Head Estate in 2009 with our daughter Ella, who was three years old at the time. Right after we moved in, my dad was visiting – he’s a builder – and he said “it smells really damp in here…” I rang Peabody and this guy came around and said, “oh, just open your windows and don’t dry your laundry inside”. It was persistent tenant-blaming. Then he sent an industrial dehumidifier but when I plugged it in, it blew the electricity. It was ridiculous. We’ve had a back-and-forth with Peabody for years. It’s unbelievable. It was only in 2015 when we got a plumber in that we realised the scale of the issue.

Our daughter Ella’s bedroom has no insulation and it has a wall exposed to the outside. The scariest thing was moving her wardrobe and seeing the black mould behind it. With her lungs still developing! They have actually made her sick, and we will really never forgive them for that. It was most visible in lockdown, as obviously we stayed at home and she was in her room. She started having breathing problems. And they were saying “oh it’s bronchitis”, or it’s this, or it’s that. She was 14 or 15, and she couldn’t walk down Columbia Road without having to stop and take deep breaths. It was so shocking and scary. [During the pandemic] people were afraid of being outside, but then suddenly we were also afraid of being inside as well.

Dealing with Peabody is like banging your head on a brick wall, because no matter what you do, they’re not taking it seriously and they’re not doing it properly. They do bodge jobs. And they’re making people sick. It’s scandalous, frankly. The people on our estate are teachers, care workers, nurses, bin workers and cleaners, the people that keep London going. There’s so many of us with the same issues and the same illnesses. The same cause and effect. It’s not the tenants’ fault. It’s structural issues. It’s criminal to rent out homes in these conditions. It’s a violent attack on people who can’t afford to find other houses.

When we first started the tenant’s association, people were less willing to talk about their personal circumstances, but it’s great now. People speak out. Plus everybody knows each other now and we’re sharing information. It’s great to see the community coming together. Especially with Peabody’s tenant-blaming, people were ashamed before but thanks to the campaign, people realise it’s not their fault. We’re not asking for big, posh homes. We just want safe, warm homes which can be a sanctuary and where you can invite your friends and family, and go to bed feeling that your children are safe. That’s not a big ask. If they’re taking rent from you, landlords should be providing that.

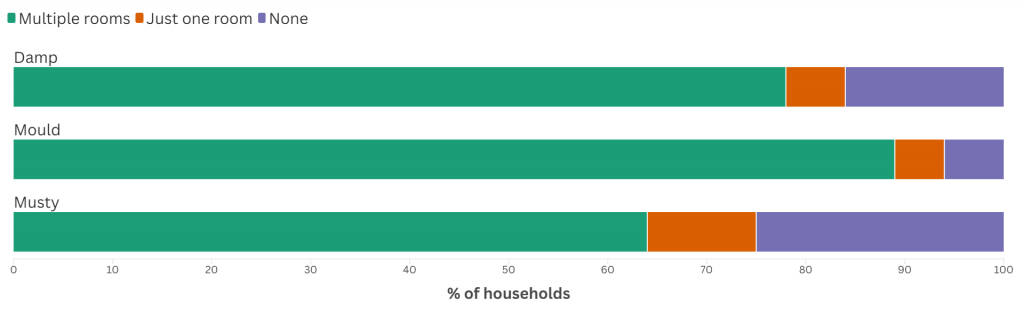

As Figure 2 shows, a total of 83% of households reported the presence of damp. Of these, just under 6% had only one room of the house affected, while almost 78% reported multiple rooms affected. Asked about mould contamination, a shocking 95% of households reported visible mould. Of these, just 5% said only a single room was affected, whereas 89% of households had multiple rooms impacted. Of those households reporting mould presence, 91% said the area affected was larger than the size of a postcard (6″x 4″). Three quarters of households (75%) reported having to live with a mouldy/musty smell in their home as a result of these conditions. Of these, just 11% said only one room was affected, while 64% said multiple rooms were affected.

Most households reported that mould issues were longstanding, with some dating the onset of the problem to as far back as 2009. The lack of adequate insulation and ventilation in many of the properties, particularly around the windows, appeared to be one factor contributing to persistent mould growth and pooling of water on windowsills. Appendix I presents further photographic evidence of some of the many instances of mould and damp that tenants on the Nags Head estate drew attention to in their homes.

We also asked residents specifically if they had difficulty keeping their homes warm, to which 74% of tenants responded affirmatively. Poor insulation is likely one factor contributing to this problem, though high energy bills will also be a significant driver.

Leaks, disrepair and other issues

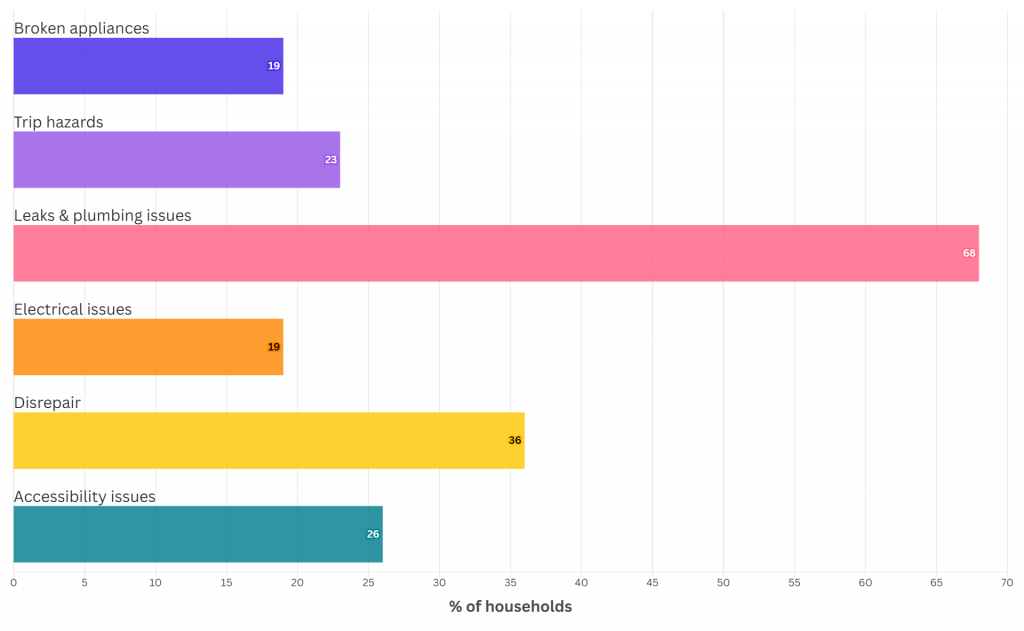

The majority of tenants reported multiple additional issues with their properties. Figure 3 shows the most commonly reported problems, besides those already discussed.

The most common issues are related to leaks and plumbing. Experience’s like Abdul’s story illustrate the suffering and indignity that living without hot water or with serious leaks inflicts on families, and the health risks posed. The fact that more than two thirds (68%) of households on the estate reported current plumbing problems or leaks shows that stories like this are all too common.

In at least three of the six blocks on the estate, insufficient cleaning of gutters has caused drains to become blocked, leading water to cascade down the outside of the buildings. In two blocks, Jellicoe House and Haig House, water had penetrated the walls leading to damp and mould growth both inside tenants’ homes and externally, around pipes, causing damage to brickwork.

Abdul’s story

I moved to Nags Head in 2009, with my wife and three children. Until 2015, the Peabody service was good. Repairs were dealt with on time. But after that, things changed. In 2023, I was having chemo. The hot water in the bathroom stopped working. I was feverish, and regularly in lots of pain. I’m a Muslim, and I have to be clean to pray. I’ve got COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), too, so if I catch a cold, I could very quickly catch pneumonia. So not having hot water is a health risk. I had to boil it with the kettle and put it in a bucket. It was so hectic, honestly it was so hectic. I complained to Peabody. I called, I emailed. The housing estate officer didn’t even reply. I got the tenants association involved because I was ill. Then Peabody sent a plumber, and then a different one. We had five weeks of no hot water in total.

Around the same time, in December, my daughter’s bedroom ceiling started leaking [photo in Appendix I]. I was complaining to them but they weren’t fixing the problem. After two, three weeks, we still had the leak and the mould on the ceiling was getting bigger and bigger. My daughter has a health issue. She’s got asthma and she was getting asthma attacks. The room smelled from the damp. I was worried the ceiling might fall in. Months went by. By May, I had an argument with them, I was so angry. I said “there is some kind of pipe leaking or something”. But they didn’t listen to me. They laughed at me. I said “if anything happens to my daughter, you are responsible”. Eventually they found a leak, as I had said! But kept delaying the repairs. We were supposed to be in temporary accommodation for two weeks but in fact it was six weeks. And by the time the ceiling was actually replaced it had been a year.

In 2021, my kitchen window was broken. It would not shut. I called them several times. First they tried to fix the mechanism, then they ordered a new one. The window was not safe, it could have easily fallen and hurt someone. So after a couple of months, they put a temporary hinge in to stop it falling. But we live on the ground floor so anybody could have come in! We could not get sleep because of it. It took them one and a half years! One and a half years I was calling, fighting, swearing. Finally they ordered a whole new window, but that took another six months, so actually it took two years to fix my window. This is what every tenant in Peabody has to suffer. We live like we’re in a prison and we have to pay for it. Without the tenants association, Peabody wouldn’t do anything at all.

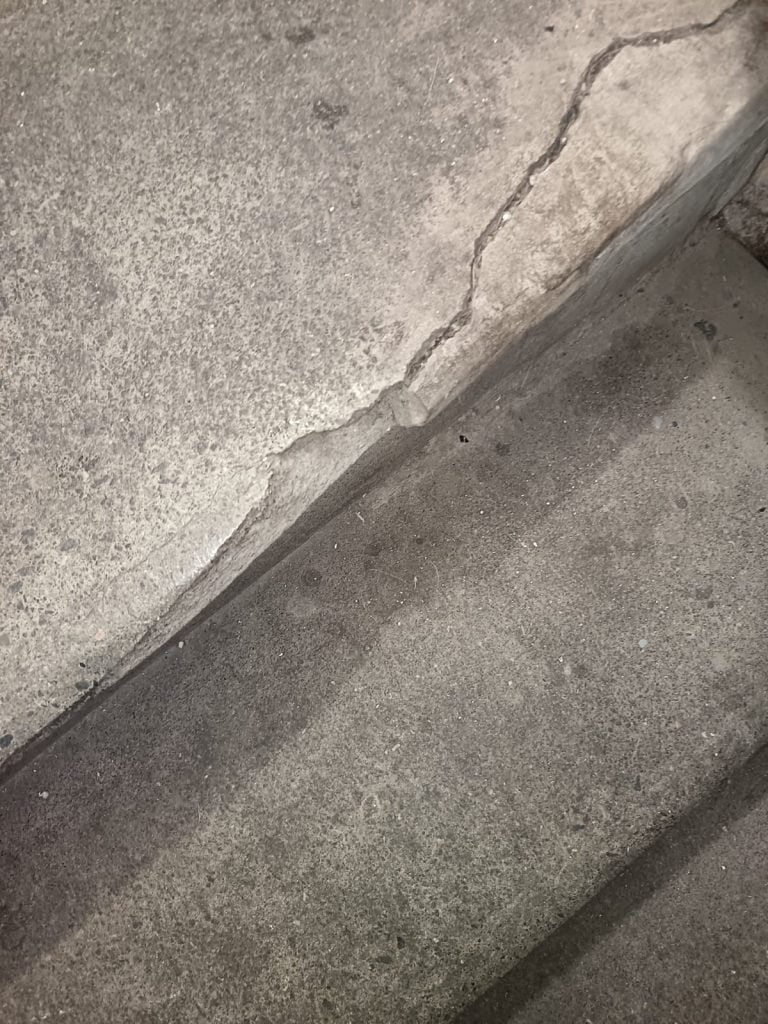

More than a third (36%) of households reported current issues of disrepair. In some cases, disrepair has been linked to injuries. In March last year, for example, Big Issue magazine covered the Nags Head Tenants Association’s fight to improve their living conditions, and highlighted the story of 19-year-old Khadija Hussain-Chowdhury who fractured her foot when a stairwell gave way.[12]

Infestations reported on the estate included bed bugs, biscuit beetles, cockroaches, wasps, mice and rats. While this issue came to light after completion of our survey, meaning complete statistics are not available, at one point in December 2024 we received reports of pest issues in at least 13 households across the estate. It appears this issue was exacerbated by the inadequate bin system – which includes open-topped bins stored in close proximity to tenants’ homes – and longstanding neglect of the building in terms of pest-proofing sheds, electrical cupboards, and entry points such as breeze bricks and drains.

Accessibility issues, reported by 26% of households, are discussed later in this report, in the section focused on the impact of disrepair and neglect on disabled tenants.

3. Health impacts

“I was once told by a doctor I had ‘Peabody Asthma’”

– Nags Head resident

Physical and mental health

There is a high prevalence of chronic health conditions on the Nags Head estate. In 57% of households, at least one person lives with at least one condition that has lasted a year or more and requires ongoing medical attention or limits daily life. Of these, 70% cited mental health issues such as chronic stress, anxiety and depression, 52% cited a respiratory condition such as asthma or COPD, and 13% cited cardiovascular conditions. Less than a third (29%) reported having their condition before moving to Nags Head.

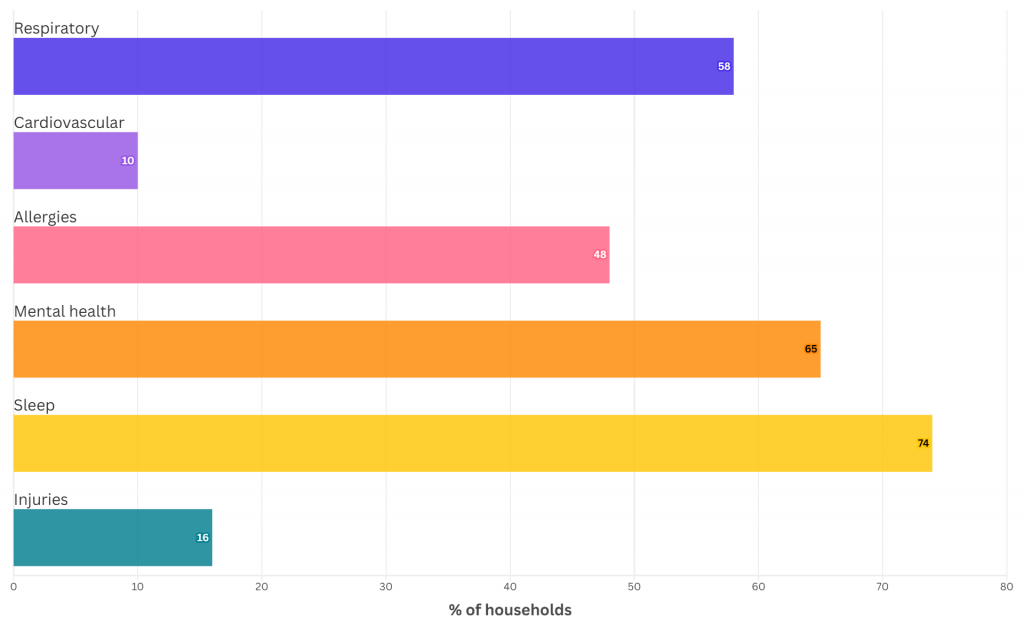

Tenants were also specifically asked whether any members of their households had developed any new symptoms (not necessarily chronic) since moving to Nags Head. In total, an alarming 86% of households reported new symptoms or injuries since moving into their properties. As Figure 4 shows, nearly three quarters (74%) cited sleep-related problems. Sleep deprivation, which can be caused by noise pollution due to inadequate thermal and sound insulation, is directly linked to increased risks of depression and anxiety.[13]

Close to two thirds (65%) experienced mental health difficulties. Living in a cold, damp, mouldy, leaky, overcrowded or infested home often means living with constant anxiety. Children living in overcrowded homes are more likely to be stressed, depressed, and have more behavioural problems and worse attainment at school than those in uncrowded homes.[14]

As qualitative data such as Tolulope’s interview testimony illustrates, people also experience feelings of shame and embarrassment as a result of blaming themselves for their housing conditions. Combined with the disincentive to invite visitors caused by the housing conditions themselves, this may lead to social withdrawal, isolation and loneliness. We also received anecdotal reports that the financial strain of tenants feeling compelled to pay for new furniture, redecoration or temporary repairs exacerbated mental health conditions. The greater burden of domestic labour – for example, of regularly having to wipe away condensation and mould, or dehumidify bedrooms while children are at school – was another contributing factor, and appeared to disproportionately affect women.

Box 1: Tenants’ accounts of how their housing damages their health

- “The damp and mould make it difficult to breathe at night sometimes.”

- “The mould is making my COPD and breathing issues worse. It is very stressful – it has been hard to get on with treatment.”

- “Cold makes [my] arthritis worse.”

- “Anxiety and depression due to continuous problems with flat.”

- “Younger son sneezes a lot, more in winter time because of damp. Older son has a very blocked runny nose, both have a bit of a cough, after using heating there is steam everywhere, no formal diagnosis of asthma, worse in winter. The wall is very damp.”

- “Damp and mould has been a huge stress.”

- “Overcrowding, mould, temperature issues, stress of small space.”

- “Asthma is bad due to mould and damp.”

- “Breathing constantly affected, chest and heart pains, eczema flaring up.”

- “I was once told by a doctor I had ‘Peabody Asthma’.”

- “Situation with pests has led to stress and anxiety.”

- “Baby in hospital with wheezing… constantly off work due to sickness.”

- “No basin in the bathroom nor radiator or shower. Barely space to move about. Lower back and shoulder pain gone worse due [to] reaching over and constant cold. No space for cooker and freezer or space for proper sofas.”

- “The persistent damp and mould must be a factor in my recurrent health issues.”

- “It’s always cold, it’s just not an adequate temperature. My son has always got a cold, sore throat, sore eyes. I find it hard to keep his body warm. His hands are always cold. I keep using oil heaters but as soon as I switch them off the room gets really cold. He had to be on antibiotics twice as he had chest infections… he will have a cold maybe once every four weeks. I have to constantly give him Nurofen as he always has a fever.”

Tolulope’s story

I’ve lived on Nags Head for 16 years. For the past… six or seven years, the house has just been going downhill… I feel like it is just breaking down around me and my kids. It’s cramped, there’s not enough space for us. Things are always breaking down and not working properly. It feels like it’s a battle of me against the home, and the home is winning, because there’s always something going wrong – the mould, the shower constantly breaking, my boiler breaks down every winter. There’s always something… that’s part of the reason why I’ve had to go part-time [at work], because there is always something needing to be repaired, so I can’t come into work. It was affecting my job.

For years I was having a lot of rodent problems. I used to call Peabody, and they would come round for about two, three seconds and pop a little thing [trap] here and there. But that never solved anything. It was a never ending battle. We used to go and stay anywhere, just to avoid being home because it was just horrible. I was spending so much of my own money trying to get rid of them. Eventually, I did a lot of research, and me and my friend used duct tape and green foam. It literally took us hours to fill up every single hole in the kitchen. My flat did not look nice, but it solved the problem. Peabody just didn’t deal with it. They didn’t do anything. So I just kept on dealing with myself. I was so depressed, and my kids were depressed. It caused me so much stress. There were some points when I was living on antidepressants.

I can’t remember the last time we had visitors. I’ve never, ever let anyone come in to visit me and my kids. We’ll meet people anywhere else but no one ever comes to visit us. I just won’t allow it, because it’s just a mess. I’m always giving excuses to meet somewhere else. We’re not living… I can’t call it living, we’re just managing and we’ve got a roof over our head. I’ve given up on Peabody. They should do more than what they’ve done. Before the Nags Head Tenants Association started, I really thought that I was the only one living like this. I felt so ashamed. Now I know that my neighbours and friends are going through the same thing.

While just under half (48%) listed allergies and one in ten (10%) cardiovascular conditions, perhaps most worryingly almost three in every five households (58%) reported a member of the household developing a respiratory condition since moving to Nags Head. The significant contribution of damp and mould to various respiratory conditions emerges clearly from the testimonies in Box 1. Disturbing details include a wheezing baby who needed hospitalisation, children and young people living with persistent coughs and colds, and older people whose arthritis is aggravated by the cold.

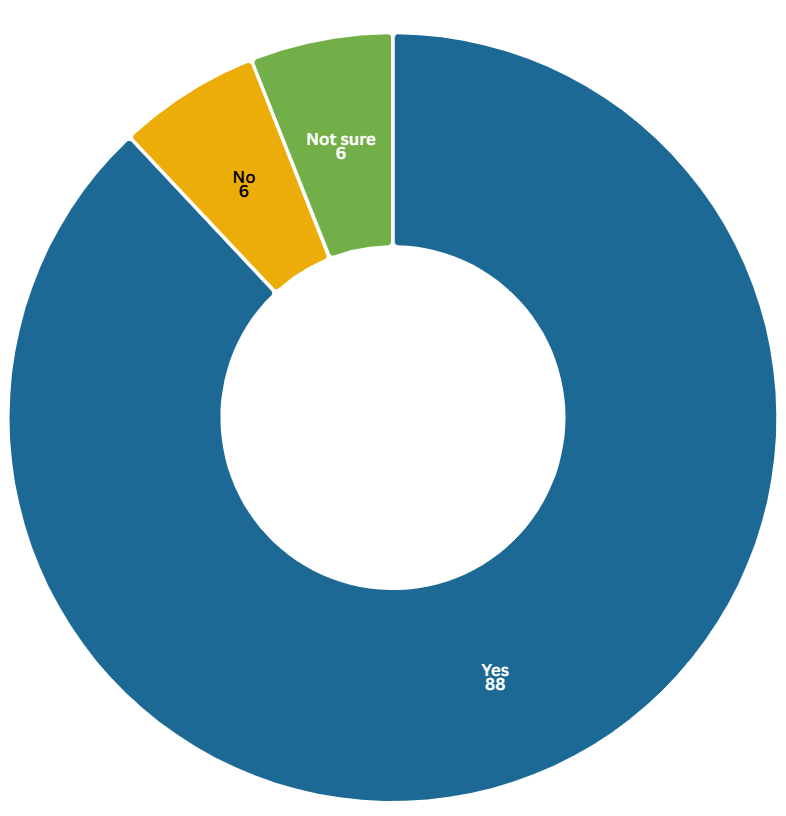

Residents did not need to be familiar with the extensive academic literature on the relationship between poor housing and poor health to understand the connection. Their daily lived experience made this clear. When asked about chronic conditions more than two thirds (68%) of respondents believed that their housing conditions had made their health conditions worse. Unsurprisingly, when asked about conditions that had started since moving to Nags Head, the proportion who felt their housing conditions had contributed rose to 88%, as Figure 5 shows. Notably, it seems that health workers, too, are lamentably familiar with the health problems associated with poor housing and negligent landlordism. As shown in Box 1, a doctor once reportedly diagnosed one survey respondent with what they dubbed “Peabody Asthma”.

Fatima’s story

I moved to the Nags Head Estate in June 2009 from west London. I’d just had a baby. Within a month, I was starting to cough whenever I entered the house and I didn’t know why. I went to the GP many times, to find out what was wrong with me. He said maybe I had a cold. After that, I was having pain and breathing difficulties… an ambulance came and took me to the hospital. That was the first time a doctor said to me “you’ve got asthma”. I said “How? I never had it in my childhood.” It had started when I moved to Nags Head.

Another issue my family had been dealing with for years is leaking water which affects the electrics in the flat. The water drips down and practically every other day something breaks because of it. I have to call them to report the washing machine stopped working, or the lights have gone, because the water has gotten into the electrics. One time it happened, they turned off my gas for three days. Last time, there was no water and no light for three days!

Most recently, they moved me and my family out for two months to finally carry out some repairs. Some of the work they did was completely inadequate. We can no longer open the bathroom window at all, and we’re waiting for them to come and fix the toilet again. And, when we came back, some of our stuff was damaged or completely missing. They threw away all the stuff for the bathroom, for example. And they’d never given us an inventory. When I complained about it, I waited months and then Peabody came back to me saying there was nothing in storage. So I’ve had to spend a lot of money from my own pocket to replace the stuff that they damaged all over again, little by little. A kitchen bin, a television, the washing machine and a desk for my daughter. We’re on Universal Credit so this is a huge financial burden. It’s a lot, both mentally and physically. The stress affects my body, it affects everything.

Mostly, I’m scared for my children. I don’t want them to be ill like me. I don’t want them to suffer. The lack of ventilation creates so much condensation, there are pools of water on my windowsills in every room of the house. My oldest son hit his head when he slipped on a pool of water in the bathroom. The mould is worse than before the repairs happened and the damp patch on my daughter’s wall is coming back. It’s already damaged school certificates and her school books. She has to keep them stored in plastic boxes now and she suffers every night with nasal congestion. Her younger brothers sleep in rooms with water dripping down the walls. My youngest son just developed a rash which I think is caused by the damp and mould in our home. He’s only four years old.

Impact on disabled tenants

The social model of disability explains that people are ‘disabled’ by barriers in society that exclude and discriminate against them.[15] Disabilities can include physical and mental differences, including chronic illnesses and neurodivergence. There are 16 million disabled people in the UK (approximately one in four people),[16] who are statistically more likely to live in social rented housing, with around a quarter renting from the council or a social landlord.[17] Homes that are suitably adapted for disabled people improve both their physical and mental health outcomes, including by reducing social isolation.[18] However, 91% of homes do not provide even the most basic accessibility features that make a home ‘visitable’, let alone suitable for disabled people to live in.[19]

In total, just over one in four (27%) Nags Head households surveyed reported a disabled person living in the property. They likely made up the vast majority of the 26% of households who reported accessibility issues on the estate, as shown earlier in Figure 3. Direct observations and anecdotal evidence suggest that the poor maintenance of the estate in general severely inhibited some disabled tenants’ freedom of movement. Issues included damage to tarmac and paving in communal areas, with holes and uneven surfaces posing difficulties and hazards to wheelchair users. More specifically, over two thirds (67%) of households with disabled residents or people with chronic health conditions believed that their housing was making their condition worse. Some disabled tenants provided examples of how their homes posed accessibility problems, shown in Box 2.

Box 2: Disabled tenants’ examples of accessibility issues in their homes

- “Unable to use the bathroom or kitchen smoothly and lack of space for essentials.”

- “No adaptations, no bar at the entrance, entrance floor uneven which led to a fall resulting in injuries.”

- “Bathroom is too small and basically derelict.”

- “Don’t take showers because I’m afraid of falling because of epilepsy.”

When reporting issues, some disabled tenants who wanted to speak to a named employee over the phone told us they were left feeling isolated and without the support they needed due to Peabody’s heavy reliance on automated digital communications, including a high turnover of app-based methods. Nonetheless, the majority (65%) told us they had informed Peabody about their disability and requested adjustments or adaptations to their property to meet their accessibility needs.

However, as Box 3 shows, when asked about Peabody’s response to such requests, tenants’ accounts were highly critical. Their testimonies raise concerns about a failure to safeguard and support disabled tenants to access the adjustments they need in a timely, respectful and effective manner. The lack of support provided by Peabody to disabled tenants prompted Medact to refer them to Disability Rights UK for support, including basic signposting to council services such as occupational health assessments or social care support.

Box 3: Excerpted responses to the survey question ‘What was Peabody’s response when you requested adjustments/adaptation to your property?’

- “Nothing.”

- “No adequate response.”

- “Peabody didn’t want a medical letter to be sent to them.”

- “We’ve asked them repeatedly to deal with damp and mould and they have not done this sufficiently [tenant suffering from chronic respiratory health condition].”

- “Ignore.”

- “Can’t adapt because my house is too small.”

- “Occupational health therapist reported two years ago. No change since then.”

- “No response.”

- “Requested to have shower changed. Did the occupational health form about three months ago but still waiting. Peabody offered to put a handrail but didn’t offer to change the bathtub.”

- “Not sympathetic.”

- “[I have been told it’s] not possible to make adaptations due to lack of space. I need to be moved.”

- “They told me I needed to do it myself as it wasn’t their responsibility.”

4. Issue reporting and resolution

While the previous section pointed to the failure of the landlord, Peabody, to ensure that requests for accessibility adjustments were responded to appropriately, disabled tenants were not the only ones left feeling ignored. Raising any other housing issue – such as mould, damp, leaks or disrepair – and having it successfully addressed, was reported to be a universal challenge for all Nags Head tenants.

In total, 95% of households surveyed confirmed that they had raised issues around the condition of their property. Unacceptably long delays in responding to and addressing housing issues were repeatedly described. Box 4 provides some tenants’ accounts of the length of time Peabody – or the various outsourced contractors charged with conducting its repairs – took to respond to issues.

Box 4: Excerpted responses to the question ‘How long did you have to wait before your landlord took action?’

- “Months.”

- “[For] a month [we had] no hot water in the bathroom. Had to shower with a kettle.”

- “Reported [issues with mould] in January, never showed up until March.”

- “Four to five months for the thermostat.”

- “Took months for them to come. They came to put a cistern [in] that does not work.”

- “Serious leak was two days (wasn’t fixed properly). Four months for the kitchen floor. Mould reported in 2021 took six weeks with multiple missed appointments. The first mould report was 2016 – formally done in 2022.”

- “Months/years.”

- “Have reported ten times for mould. Been waiting for an extractor fan for the bathroom for over a year. I call every month.”

- “In the bathroom, probably eight years. For the leak in the kitchen, six months.”

- “We’ve lived here 15 years, and it’s the first time someone has come to clean the damp and mould.”

- “It was quick, but with the issue of pests they will always come but issues will not be resolved.”

- “Two months”

- “Still waiting. Estate manager came in a month ago. Have not heard from them.”

Tenants reported that Peabody representatives approached problems as “lifestyle issues”, for example by implying residents were to blame for mould and damp when homes were close-to impossible to properly ventilate. Medact researchers also witnessed these attitudes expressed in comments made by Peabody representatives at an open meeting.

Furthermore – even when housing issues were eventually addressed – when asked whether these issues were resolved, only 3% of households responded affirmatively. As Figure 6 shows, the remaining households reported that their issues had either been only partially resolved (24%) or, in the vast majority of cases (73%), remained unresolved. Box 5 provides examples of tenants’ accounts of their experiences of poor, or non-existent, issue resolution.

Notably, 88% of tenants told us they had never reported their housing issues to Tower Hamlets council directly. This highlights a lack of accessible information for tenants about the duty of councils in relation to enforcement of housing standards, particularly when issues are not being adequately addressed by a social landlord.

Box 5: Excerpted responses to the question ‘If you have contacted your landlord [about housing issues], how did they respond?’

- “Nothing has been done.”

- “Came once and never turned up again.”

- “It was all down to me to fix these problems.”

- “[It] took very long and issues were never resolved properly.”

- “Never answer the calls. Have only managed to contact them once. Call the central Peabody office but never managed to get through. They said they handed the matter to United Living but did not hear from them for the next three months.”

- “Heating issues have not been addressed. The windows in the bathroom are broken and despite reporting this for years this has not been addressed.”

- “Someone will come around. People come look at it and [it] never gets addressed. Wrong people come and visit without knowing about the problems. They will constantly visit but never repair anything.”

- “Sometimes they don’t respond at all, sometimes they call. They spray the mould but it comes back. I called them eight times about the broken window. They said they would fix it but they still haven’t after four months”

- “The mould issue is ongoing.”

- “After three months they have attended the property but not taken any actions to resolve the problems.”

Importantly, the persistent stress and anxiety of experiencing longstanding disrepair and other problems were compounded by the lack of adequate response. Most Peabody communications were via phone calls, generally from private numbers, meaning tenants never had a written record of conversations, found it hard to process the content of calls, and struggled to evidence what had been discussed. Another example of insufficiently accessible communication was that phone conversations created barriers for non-native English speakers.

Moreover, tenants expressed feeling ignored by the landlord when requesting repairs, frustrated when subcontractors did not show up to appointments, anxious about not knowing when, or if, issues would be rectified, and despairing when ‘repairs’ did not actually resolve the problem. A continuous thread connecting the testimonies provided by Helena and Kevin, Abdul, Tolulope and Fatima is the need to fight intensively to have problems addressed, only for Peabody or its agents to carry out what the former refer to as “bodge jobs”. Indeed, as Box 6 shows, some tenants surveyed explicitly identified Peabody’s response (or lack thereof) – the length of the waits for repairs, persistence of problems and sense of powerlessness and exasperation at being ignored – as a factor directly harming health.

Box 6: Tenants’ accounts of the mental health impacts of poor issue resolution

- “Mental health suffered as a result of complaints not being addressed.”

- “It took eight months for the issue to be resolved which severely affected my mental health.”

- “It’s been a huge stress on us dealing with the housing issue.”

- “Anxiety and depression due to continuous problems with flat.”

- “The lack of response [from Peabody] leads to anxiety and depression.”

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The data in this report exposes the long-term neglect of the Nags Head estate and the devastating health impacts – on both adults and children – of Peabody’s failure in its duties as a landlord. Most of the health harms documented are wholly preventable but effective interventions to address underlying structural causes have rarely been forthcoming. Instead, our findings show a pattern of victim-blaming, whereby tenants themselves were held to be responsible for the housing problems they had sought to have rectified in order to legitimise their landlord’s failure to address issues appropriately.

Critically, Peabody’s chronic underinvestment in essential repairs has occurred over a period of years during which it has simultaneously grown to become one of the largest landlords in Britain. Like other similar organisations, Peabody has focused on acquiring other housing associations and developing shared ownership properties, leaving its existing stock in disarray at the expense of low-income tenants. In just the last two years, this has resulted in several damning rulings by the Housing Ombudsman against Peabody in relation to other properties it manages.[20] Yet while it bears huge responsibility, unfortunately for social housing tenants across the country, most of the housing and health issues presented in this report are far from unique to Nags Head, or even to Peabody properties.

The roots of the problem are systemic. The state of housing in Britain is a national health emergency, one created by government policies pursued over several decades, as Medact’s briefing The Public Health Case for Social Housing explained. Since 2010, government austerity measures have significantly cut funding for social housing. This has led to housing associations struggling to maintain properties due to reduced budgets. Additionally, local councils, which used to oversee social housing, have faced severe budget cuts, reducing their ability to inspect and enforce housing standards. The failure to build enough social housing forced many tenants into overcrowded, unsuitable homes. Simultaneously, the Housing and Planning Act 2016 weakened government oversight of housing associations by reducing regulatory intervention, enabling many to shift towards commercial models, prioritising new developments and financial growth over maintaining existing homes and accountability to tenants.

The social murder of Grenfell Tower, whose residents had raised fire safety concerns but been ignored, and the preventable death of Awaab Ishak in Manchester, after his father’s repeated complaints about dangerous black mould went unheeded, provide stark examples of the consequences of unaccountable landlords ignoring their tenants. All too often, residents affected are from racialised communities. In this sense, the Nags Head case study is a microcosm of the wider housing crisis.

However, the story of Nags Head is also a story of hope. Through the tenants association, Nags Head residents have relentlessly organised and advocated for their housing rights. Overcoming multiple barriers, they have called out Peabody’s failures and won changes with the potential to lead to meaningful change. These changes include a budget being allocated towards estate improvement and investment works, independent surveyors visiting residents, and an in-sourced repair team being based on the estate twice a week, alongside promises to improve tenant engagement. While the recommendations below outline what else Peabody must urgently do, the tenants’ inspiring struggle highlights the importance of collective action – which breaks dynamics of individualised isolation and shame, lays bare underlying structural drivers of shared problems, and enables people to support and learn from each other in the fight against housing injustice.

Recommendations for Peabody

Safe, warm homes

- Retrofitting: immediately create a comprehensive plan to retrofit all homes.

- Consultation: ensure this happens in proper consultation with tenants, to ensure they are involved in decision-making around interventions.

- Ventilation: alongside improvements to insulation and energy efficiency, the plan must ensure homes have adequate ventilation in order to prevent condensation buildup, damp and mould growth.

Adequate maintenance

- On-site repairs: strengthen the presence of on-site repair teams to reduce delays and improve service quality e.g. through permanent surgeries.

- Caretaker capacity: expand on-site caretaker and maintenance teams to ensure proper waste management and cleaning of communal areas.

- Cyclical maintenance: ensure regular upkeep of essential infrastructure such as roofs, gutters, drains and communal spaces.

- Waste management & pest control: implement effective measures to eliminate infestations e.g. pest proofing, bin redesign and bin capacity.

- Communal areas: secure and make fit for purpose communal areas such as bike sheds, storage units, community launderette, and develop them for community benefit.

Support for disabled tenants

- Access to occupational assessments: help disabled tenants access assessments from occupational therapists for acute and urgent needs.

- Prompt adjustments: make simple adaptations to properties – such as grab rails at entrance doors – in a timely way, to prevent accessibility issues becoming more acute physical and mental health concerns.

- Access to council support: support disabled tenants through the process of obtaining a council needs assessment in order to access a full property assessment, support from social care or the Disabled Facilities Grant for aids and equipment, and more complex adjustments or rehousing if needed.

- Training: ensure staff undergo training in the social model of disability to prevent them blaming tenants for their needs.

Recommendations for other stakeholders

Local authorities

- Right to escalate: conduct an information campaign to raise awareness and ensure housing association tenants know of their right to escalate issues related to poor standards to the council when unaddressed by landlords, including housing associations.

- Enforcement: make greater use of environmental health teams’ enforcement powers to intervene in situations where private or social landlord neglect is affecting the health and safety of tenants.

NHS bodies

- Information sharing: ensure health workers who become aware of housing situations causing or exacerbating health conditions – such as damp and mould or accessibility issues – are equipped to signpost tenants to information and resources.

- Referrals and escalation: improve housing and health reporting pathways and mechanisms so that health workers can make referrals and escalate long-standing health issues where necessary.

Appendix I: Photos of Nags Head housing issues

Left: Example of condensation on windowsills in Haig House – widespread problem in the Nags Head estate. Right: Example of crumbling stairs at Sturdee House – several incidents have been reported as a result of this.

Left: Example of mould around a window area in a flat in Haig House. Right: Example of Mould in a bedroom corner in a Flat in Jellicoe House.

Left: Example of mould around a window in Sturdee House. Right: Example of poor repairs in a flat in Haig House following repairs.

Left: Example of condition of property in a flat in Jellicoe House after repairs to address mould. Right: Back of wardrobe in a home in Sturdee House.

Left: Waste management systems lead to overflowing bins and fly tipping. Right: Bathroom in estate in a state of disrepair.

Left: Evidence of Abdul’s leak in his daughter’s bedroom. Right: Moss growth on brickwork caused by leaky gutters at a property in Maude House.

Appendix II: Nags Head in the Media

“Sick tenants confront social landlords at awards show”, Channel 4, November 2023: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5WWozPJKfYE.

“Housing estate plagued by mould, damp and dire conditions. Now, residents are fighting back”, Big Issue, March 2024: https://www.bigissue.com/news/activism/tower-hamlets-estate-horror-mould-fighting-back.

“Mould is political”, New Economics Foundation, March 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bJRGWdmVfk.

“The estate where tenants are taking collective legal action on damp and mould”, Inside Housing, July 2024: https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/insight/the-estate-where-tenants-are-taking-collective-legal-action-on-damp-and-mould-86481.

“Nags Head estate residents’ health deteriorates due to mould and bed bugs”, The Slice, September 2024: https://bethnalgreenlondon.co.uk/nags-head-estate-residents-protest-peabody-over-repairs-health-issues.

Notes & references

[1] Krieger, J. & Higgins, D. L. (2002) “Housing and Health: Time Again for Public Health Action”, American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 758–768.

[2] Qadri, M. “Nine million spent Christmas in ‘Dickensian’ housing conditions, survey finds”, Independent, 29 November 2022, available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/christmas-cold-electricity-heating-bill-b2252577.html; “What is the Housing Emergency”, Shelter, n.d., available at: https://england.shelter.org.uk/support_us/campaigns/what_is_the_housing_emergency.

[3] Clair, A. & Hughes, A. (2019) “Housing and health: New evidence using biomarker data”, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(3), 256–262; Marmot, M. et al. (2020), Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On, Institute of Health Equity.

[4] Fisk, W., Eliseeva, E. & Mendell, M., (2007) “Association of residential dampness and mold with respiratory tract infections and bronchitis: A meta-analysis”, Environmental Health, 6(1), 70; Mendell, M., Mirer, A., Cheung, K., Tong, M. & Douwes, J. (2011) “Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: A review of the epidemiologic evidence”, Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(6), 748-756; Shiue, I. (2016) “Cold homes and cardiovascular disease risk factors: Results from the UK Household Longitudinal Study”, Public Health, 136, 131–133.

[5] Garrett, H. et al. (2021), The cost of poor housing in England, Building Research Establishment, available at: https://files.bregroup.com/research/BRE_Report_the_cost_of_poor_housing_2021.pdf.

[6] “Medact Research Policy” (2020), Medact, available at: https://www.medact.org/our-work/research.

[7] “Research Code of Ethics” (2023), Human Impact Partners, available at: https://humanimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/HIP-Research-Code-of-Ethics.pdf.

[8] According to the latest figures from the English Housing Survey.

[9] Gove, W., Hughes, M. & Galle, O. (1979) “Overcrowding in the home: An empirical investigation of its possible pathological consequences”, American Sociological Review, 44(1), 59-80; Solari, C. & Mare, R. (2012) “Housing crowding effects on children’s wellbeing”, Social Science Research, 41(2), 464-476; Baker, M., McDonald, A., Zhang, J. & Howden-Chapman, P. (2013) Infectious Diseases Attributable to Household Crowding in New Zealand: A Systematic Review and Burden of Disease Estimate, Wellington: He Kainga Oranga/Housing and Health Research Programme, University of Otago.

[10] Balogun, B. et al. (2023) “Health inequalities: Cold or damp homes”, House of Commons Library, available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9696/CBP-9696.pdf; Clark, S. et. al. (2023) “The Burden of Respiratory Disease from Formaldehyde, Damp and Mould in English Housing”, Environments, 10(136).

[11] “Damp rented homes are increasing children’s risk of ill health” (2023) Chartered Institute of Environmental Health, available at: https://www.cieh.org/ehn/housing-and-community/2023/november/damp-rented-homes-are-increasing-children-s-risk-of-ill-health.

[12] McRae, I. (2024) “Housing estate plagued by mould, damp and dire conditions. Now, residents are fighting back”, Big Issue, 12 March 2024, available at: https://www.bigissue.com/news/activism/tower-hamlets-estate-horror-mould-fighting-back.

[13] Pires, G., Bezerra, A., Tufik, S. & Andersen, M. (2016) “Effects of acute sleep deprivation on state anxiety levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, Sleep medicine, 24, pp.109–118; Babson, K., Trainor, C., Feldner, M. & Blumenthal, H. (2010) “A test of the effects of acute sleep deprivation on general and specific self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms: an experimental extension”, Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 41(3), pp.297–303.

[14] Solari, C. & Mare, R. (2012) “Housing crowding effects on children’s wellbeing”, Social Science Research, 41(2), 464–476.

[15] “The Social Model of Disability”, n.d., Inclusion London, available at: https://www.inclusionlondon.org.uk/about-us/disability-in-london/social-model/the-social-model-of-disability-and-the-cultural-model-of-deafness.

[16] Kirk-Wade, E. et al. (2024) “UK disability statistics: Prevalence and life experiences”, House of Commons Library, available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9602/CBP-9602.pdf.

[17] “Disability and housing, UK: 2019” (2019) Office for National Statistics, available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/bulletins/disabilityandhousinguk/2019.

[18] Heywood, F. (2004) “The health outcomes of housing adaptations”, Disability & Society, 19(2), pp.129–143.

[19] Davies, L. (2023) “Accessible homes are a matter of social justice”, Centre for Ageing Better, available at: https://ageing-better.org.uk/blogs/accessible-homes-are-matter-social-justice.

[20] “Leaks left children ‘caught in downpours’ as Ombudsman finds three counts of severe maladministration for Peabody” (2023) Housing Ombudsman, available at: https://www.housing-ombudsman.org.uk/2023/10/05/three-counts-of-severe-maladministration-for-peabody; “‘Horrible’ and ‘intolerable’ conditions described by Peabody residents as Ombudsman makes 4 severe maladministration findings” (2024) Housing Ombudsman, available at: https://www.housing-ombudsman.org.uk/2024/03/05/peabody-4-severe-maladministration-findings; “Independent review at Peabody finds 180 families decanted for lengthy periods following Ombudsman wider order” (2024) Housing Ombudsman, available at: https://www.housing-ombudsman.org.uk/2024/08/29/independent-review-at-peabody-ombudsman.