A Medact Homes for Health report.

Authors: Dr Hil Aked, Dr Calum Barnes, Maria Carvalho da Silva, Jordi López-Botey.

Contents

Executive summary

1. Introduction

2. Scale of the public health crisis in our homes

3. Uneven impacts

4. Costs of living

5. Effects on health workers and the NHS

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations

Notes and references

The data used in this report is available in full in the document: Survation (2025) Survey of Healthcare Workers: Analysed by Survation on behalf of Medact.

Executive summary

- This report exposes the extent of the public health crisis caused by unhealthy homes through the first national survey of its kind: a poll of more than 2,000 UK health workers, supplemented by interviews.

- The findings reinforce existing evidence showing the urgent need to ensure healthy homes for all.

- Recommendations to the government include: build good-quality social housing; reform right to buy; start a mass retrofitting programme; implement the Decent Homes Standard and Awaab’s Law; and implement rent controls.

Key findings

- Three quarters of health workers see patients whose poor housing is likely harming their health; more than one in ten see such cases almost every day.

- Almost half (45%) have had to send a patient home knowing that their housing situation would make them ill again.

- Almost two thirds (65%) see patients living in excessively cold homes.

- More than two thirds of health workers (70%) see patients forced to go without energy because they are unable to pay bills monthly; one in ten sees this almost every day.

- More than three in five (61%) hear of damp and/or mould in patients’ homes.

- More than two thirds (70%) of health workers see mental health conditions caused or worsened by housing problems.

- More than three in five (61%) see respiratory or cardiovascular illnesses.

- Almost two thirds of health workers (64%) see children experiencing health problems likely caused or worsened by insecure housing at least once a month.

- Two thirds (67%) see children experiencing respiratory problems caused or worsened by mould or damp at least once a month; over a quarter (28%) see children in this situation weekly.

- Just under two thirds (65%) of health workers report seeing mobility issues linked to housing in older people.

- Two thirds of health workers (66%) see disabled people living in unsuitable accommodation likely causing or worsening ill health monthly; one in ten see this almost daily.

- 84% of health workers are concerned about the impact that poor housing is having on health.

- Over half (54%) believe high rents worsen chronic health conditions or delay treatment, due to knock-on effects on people’s financial situations; over two thirds (69%) think making rent more affordable would reduce impact on the NHS.

- More than two thirds (69%) agreed with the statements “I feel powerless to support my patients with their housing conditions” and “government spending to prevent illnesses created by cold homes is better for the NHS than having to spend money to nurse patients back to health”.

1. Introduction

Context

This report contains the findings of the first national survey to explore how health workers in Britain witness the housing crisis in their work. The housing crisis is multifaceted. Insecure tenancies, unaffordable rents, disrepair, poor insulation, fuel poverty, and damp and mould are widespread problems, spanning both the private rented sector and social housing, leaving millions of us living in cold, unhealthy homes.

Against the backdrop of sky-high energy bills and the wider cost-of-living crisis, Britain’s housing crisis is in turn fuelling a public health crisis.1 In December 2022, for instance, research showed that over 9 million adults were living in cold, damp homes; meanwhile, a quarter of people with health conditions made worse by such environments could not heat their homes to a safe level.2

The impacts of the public health crisis on our homes are not evenly distributed. Instead, like other socio-economic root causes of these health problems (the ‘social determinants’ of health) with which they interact – such as working conditions and education – they are profoundly unequal. Children, the elderly, disabled people, LGBTQ+ people, refugees, single parents and racially minoritised groups are disproportionately represented among the working classes who suffer most from entrenched housing and health inequality.3 The first three of these inequalities are reflected in the survey results presented here. Health worker testimonies highlight some of the others.

Every day, health workers bear witness to the multiple physical and mental health conditions caused, or exacerbated, by unhealthy homes. From increased risk of cardiovascular conditions like heart attacks, to respiratory conditions like asthma, and mental health conditions like depression, health workers do their best to mitigate the damage they see. But, as individuals, they are unable to address the social determinants of health, and can merely fight the symptoms. In effect, they are playing whack-a-mole, since they often have little choice but to send patients home to unhealthy houses, knowing their living conditions will make them sick again soon. This state of affairs takes its toll on health workers themselves, as well as patients. It also increases strain on the health system as a whole, with poor housing costing the NHS an estimated £1.4 billion every year.4 Indeed, the whole of society pays a price: the knock-on impacts of health problems associated with poor housing on childrens’ development and young people’s education have long been documented.5

This situation is wholly preventable. Chronic NHS underfunding must end, but most preventative solutions lie outside the healthcare system – in housing, energy, and social policies which could drastically improve our homes, and in the process our physical and mental health too. In previous Medact briefings The Public Health Case for Social Housing6 and The Public Health Case to Warm Our Homes, Not Our Planet,7 we traced the history of the current crises, as well as outlining policy solutions such as rent controls, insulation, affordable energy, and secure, accessible social housing. This report contains new evidence underlining the urgent need for ongoing collective action to win healthy homes for all, as part of the wider struggle for climate, housing and economic justice.

Methods

This report presents the results of a survey commissioned by Medact and Warm This Winter, the first national study of its kind to explore how the housing crisis shows up daily in the lives of health workers on the job.

Conducted by polling agency Survation online in late January and early February 2025, the survey asked a series of 16 questions to a sample of 2,128 health workers (aged 18+) in the UK.8

Questions concerned: the types of housing issues health workers most often encounter; the housing-related health problems they typically see patients experiencing; the groups of patients most commonly impacted (such as children, elderly people, and disabled people); their views on the effects on the NHS more broadly; and how they believe the problem should be addressed. We also collected demographic data, namely health workers’ age group, gender, ethnicity, region, speciality and current role. The full list of questions and survey results are available on our website.9

Alongside this survey, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a small number of health workers (n=8) who had witnessed the health impacts of the housing crisis first-hand. To protect patients, we have given these health workers pseudonyms. Their condensed and paraphrased testimonies, included throughout this report, illuminate the human cost of the public health crisis in our homes.

Several interviewees highlighted the fact that health services do not routinely inquire about patients’ living conditions, and therefore often miss opportunities to identify when housing issues are behind the health problems. Combined with the feelings of shame and stigma which may cause patients to under-report issues at home (together with reporting-fatigue, where they grow tired of raising an issue which never gets solved), it is likely that the survey results actually underestimate the extent of the public health crisis of unhealthy homes.

2. Scale of the public health crisis in our homes

Our survey revealed housing-related health problems to be so prevalent that three quarters of health workers regularly see patients whose poor housing is likely to be harming their health, by causing or worsening physical or mental health conditions.10 Of these:

- around a third (30%) encounter these cases monthly

- another third (32%) see people in this situation weekly

- and more than one in ten (12%) see such cases almost every day.

Meanwhile, just 15% see such cases “rarely” (ie less than once per month), and 8% never witness this.11

We also found that almost half (45%) of health workers have had to send a patient home knowing that their housing situation would make them ill again.12

Given the frequency with which health workers are witnessing the dire health impacts of the housing crisis, it is unsurprising that 84% are concerned about the impact that poor housing is having on patients, with just 14% saying it was not of concern.13

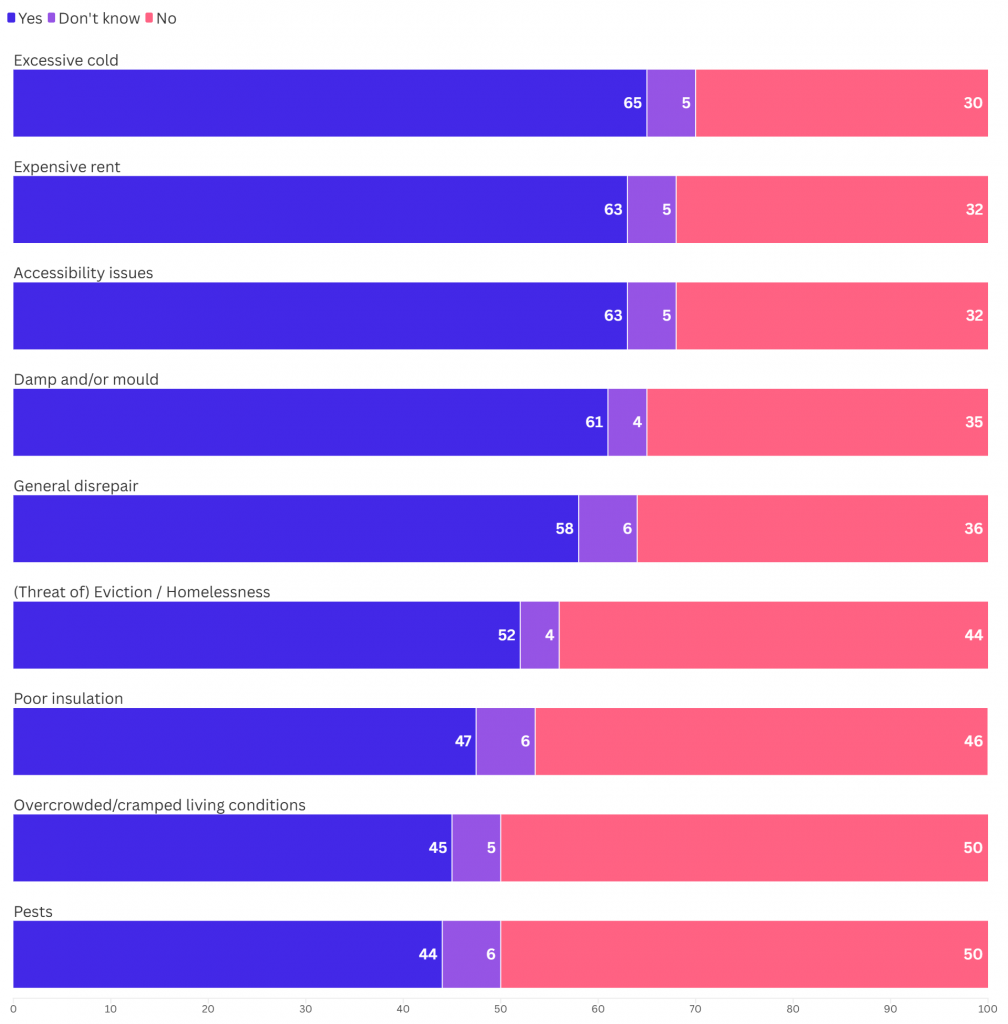

Common housing issues

In the course of seeking to treat symptoms of ill-health with which patients present, health workers will attempt to identify the underlying causes. As a result, they commonly hear patients describe their living conditions, bringing into sharp focus the numerous housing problems people across contemporary Britain suffer – problems which are likely causing or worsening their health conditions. As Figure 1 shows, asking which problems patients had described, our health workers’ poll revealed that:

- almost two thirds (65%) see patients living in excessively cold homes

- marginally fewer (63%) see patients who describe expensive rent as an issue

- the same proportion (63%) see patients experiencing accessibility issues at home

- more than three in five (61%) hear of damp and/or mould in patients’ homes

- a slightly smaller proportion (58%) become aware of disrepair in patient’s homes

- over half (52%) see patients under threat of, or subject to, eviction or homelessness

- almost half (47%) see patients with poor insulation, contributing to cold homes

- just under half (45%) see patients living in cramped or overcrowded housing.14

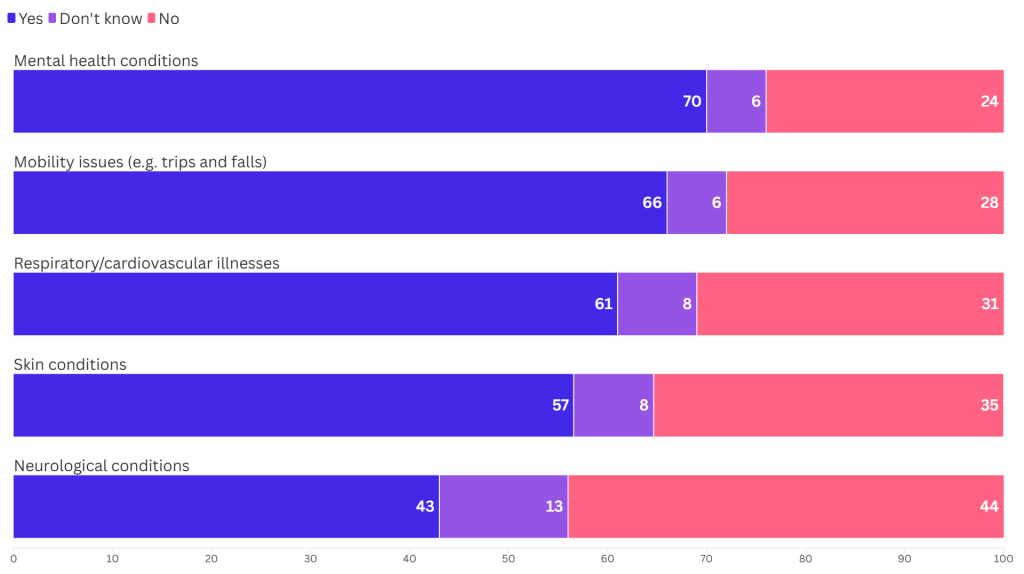

Mental and physical health impacts

Every day at work, health workers come face to face with the lived reality of housing as a determinant of health. Almost three quarters (72%) of health workers polled believe that poor-quality housing worsens chronic health conditions or delays treatment of them.15 We asked health workers about which physical and mental health issues they see which they believe are caused or worsened by housing problems. As Figure 2 shows, the results indicated that:

- more than two thirds (70%) see mental health conditions

- two thirds (66%) see mobility issues (eg trips and falls)

- more than three in five (61%) see respiratory or cardiovascular illnesses

- over half (56%) see skin conditions such as eczema

- somewhat fewer (43%) see neurological conditions.16

As noted in the methods section, these findings may actually understate the extent of the public health crisis of unhealthy homes. Reinforcing evidence from numerous previous studies, the vast scale of the problem is clear.

Sophia – clinical psychologist:

I work in parental mental health. Housing issues come up in a big proportion of the families who seek support, it’s very often a factor in why families are under huge mental strain. The same problems time and time again. Housing insecurity and precarious housing situations either to do with affordability or inaccessible social housing. I see really high rates of anxiety, stress and worry to do with housing. It often takes up so much thinking space and is completely overwhelming. If you’re at risk of being evicted from your home, it is very difficult to think about anything else. I’ve seen people having suicidal ideation – almost plans – because they feel so completely hopeless, in part caused by housing issues, or losing their home, or facing homelessness.

Overcrowding is a big problem. Children, and even adolescents, are having to share bedrooms with their parents, which puts strain on family relationships. I have seen distressed young people engaging in risky behaviours as a result of the lack of privacy and space in the home environment. Parents feel guilty that they aren’t able to provide adequate space for their children appropriate to their developmental stage, but they’re unable to change their living situation.

Another family I worked with were recent migrants to the UK and English wasn’t their first language, so they already had these barriers. Their house was completely overridden by mould. It was one of the most shocking things I’ve seen. It was a very unsafe place to live. The parents were having to bring up their children – one of whom was a vulnerable adult with learning disabilities – in a house that was literally falling apart. Unfortunately, once we pushed to get the local authority environmental team to come into the house, the landlord served them with eviction.

So yes, we should fund the NHS, but if that’s not alongside funding healthy homes, we’re not going to get very far. Huge, systemic intervention is needed. Social housing waiting lists are ridiculous because there is obviously such a lack. We need better regulations of private landlords to enforce healthy and adequate living conditions. We need rent controls to stop the landlords raising prices for pure profit.

Katie – asthma nurse:

From my experience, the children that have poor asthma control have issues around overcrowding and mould in the home. Over the years, referrals are increasing. So many people are living in environments that are highly polluted, indoors and outdoors. Some families I work with, who are living in mouldy homes, are frightened to push things as they are told by landlords, “you can leave if you don’t like it.” They fear being homeless, or unable to afford somewhere else, so end up staying there. For some people, their main worry is feeding their family, so housing isn’t at the top of their priority list. When you’ve got all these other stresses, it’s the bottom of the pile, especially if you’re not being listened to. When kids have asthma, there’s a knock-on impact on their education and on them mentally. Most children with asthma worry about having an attack because not being able to breathe is very scary, and fear hospital visits. We’re seeing more children having asthma attacks due to anxiety and panic.

A lot of families do try with the council. And often they get fobbed off that it’s their fault, or ignored. Especially families who are not familiar with their rights or whose first language is not English. So I try to advocate for them. On a daily basis, I battle with the housing associations or council. In one family I work with, there’s a child who hasn’t lived at home for the last two years because of mould in the property. It has badly affected her mental health, of course. She misses her family, and that in turn has contributed to stress and anxiety, triggering her asthma. And the family are now on medical priority to be rehoused. But there’s no houses big enough for them. So they just keep bidding and bidding, and looking and looking. After two years, the family took it upon themselves to completely rehouse her with her aunty, for her health, because she was having multiple visits to the hospital. And she’s now had to be referred to CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services). I’ve got other families that once they’ve moved into a property where there’s no mould, their asthma has completely changed, and they’ve been able to come down off treatments.

3. Uneven impacts

Importantly, these mental and physical health impacts are not evenly distributed across the population. Certain groups are more likely to experience housing issues and more likely to suffer dire health consequences as a result.

Children

Children are especially vulnerable to the health effects of poor housing. It is therefore extremely worrying that almost two thirds of health workers (64%) see children experiencing health problems likely caused or worsened by insecure housing regularly, ie at least once a month. Of these:

- close to a third (29%) said they encountered these children monthly

- over a quarter (27%) said they saw children in this situation weekly

- almost one in ten (8%) said they saw such children almost every day.

Meanwhile, less than one in five (19%) said they saw children whose housing was likely harming their health “rarely” (less than once per month), and only 12% reported never seeing this.17

In terms of the range of housing-related health problems seen in children:

- two thirds (66%) of health workers see children with mental health conditions likely caused or worsened by housing conditions

- over half of health workers (57%) see children with potentially housing-related respiratory or cardiovascular problems

- over half (55%) linked lower school attendance to housing issues

- and the same proportion (55%) witness malnutrition.18

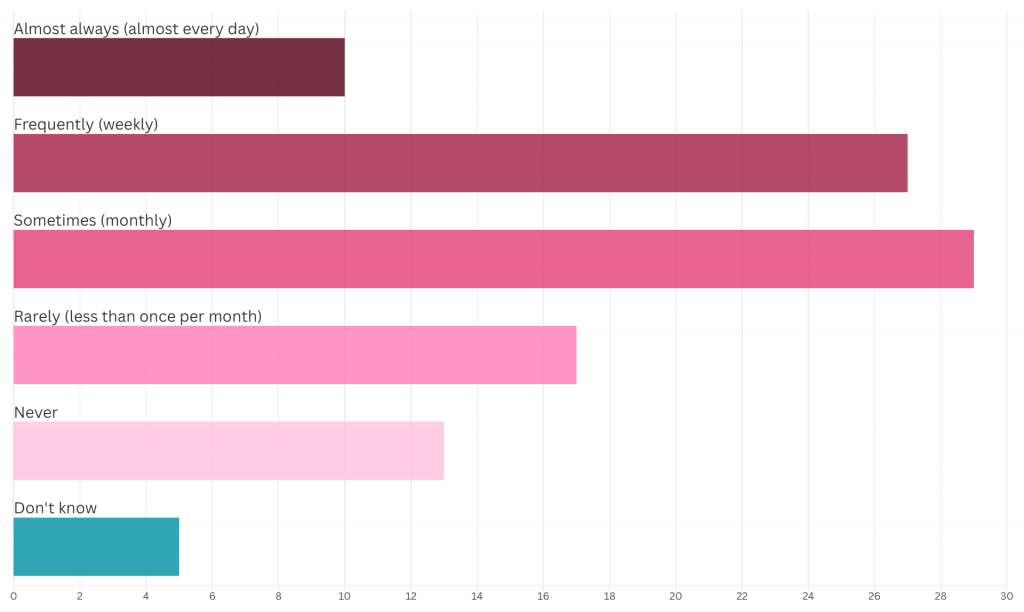

When asked specifically about mould and damp and its effect on respiratory illness, the results were startling. As Figure 3 shows, more than one third (36%) of health workers told us they see children with breathing difficulties likely caused or worsened by mould or damp in their homes at least once a week. And, in total, an alarming two thirds (67%) see children experiencing respiratory problems caused or worsened by mould or damp regularly, ie at least once a month.

Of these:

- close to a third (31%) said they encountered these children monthly

- over a quarter (28%) said they saw children in this situation weekly

- almost one in ten (8%) said they saw such children almost every day.

Meanwhile, just 19% said they saw children with respiratory problems likely caused or worsened by their housing “rarely” (less than once per month), and just 11% never see this.19

Given these appalling statistics, it is little wonder that 82% of health workers are concerned about the impact of housing on children’s health.20

Eleanor – midwife:

I’m a community midwife in an area which is quite deprived. Overcrowding is a problem. Cold and damp is a problem. I went to the apartment of a lovely couple, and they had a young baby and a toddler, and on a good metre of the wall behind the sofa, I could visibly see the mould. I remember the size of the mould very well, and that baby on the sofa literally 50 centimetres away, breastfeeding, and inhaling that thing all day was one of the saddest things I’ve ever seen. There was water actually dripping from the window. The toddler had eczema and asthma. The mum told me they were waiting and waiting, and asking and asking for it to be fixed. As a midwife, I wrote to say “they have a newborn and a toddler, so you need to do something”. It’s horrible that the only thing you can do is send a letter. I know some of my colleagues got people re-housed, or got things fixed more quickly. But in the city where I work, it’s just so frequent, most of the midwives don’t even bother anymore because they think it’s not going to change anything.

I don’t often see the long term physical health impacts of exposure to mould and damp. The main effect I see is the impact on mental health. It’s extremely stressful to have to deal with a housing association, or a council, that is doing nothing to improve your living conditions, when you can see mould on the wall, and you’ve got a newborn coming. You don’t want to expose your unborn child to this in the first days of their life. You’re maybe working two jobs to pay the bills, you don’t have the time to face this massive institution. So it impacts your mental health massively. You feel completely useless in doing anything right for your baby. People get severe depression, because they feel extremely powerless. The housing association or the council just say “it’s gonna be done”, but it’s never done.

Krishnan – child doctor:

Hospitals are where illness is treated but my experience shows me that health is created at home. As families are increasingly unable to keep up with housing and energy costs, homes are becoming sites of illness. Given everything we know about the positives of good-quality housing, I never thought I’d see a rise in Victorian-age diseases. It’s become more common to see referrals for undernutrition and malnutrition. Rickets, typically caused by vitamin D and calcium deficiencies, is on the rise, in large part because families’ budgets for essentials can’t keep up with rising costs, resulting in skipped meals and inadequate nutrition for growing bodies. The UK is experiencing some of the highest levels of childhood stunting in Europe too – that’s when children are too short for their age and often do not meet their expected adult height and development. Again, that’s directly related to undernutrition, which has deep economic and political roots.

Another disease many wouldn’t really have thought would be on the rise in the UK – but I’ve seen cases affecting children – is tuberculosis (TB). Whilst most cases usually involve travel from other parts of the world where it’s more prevalent, it’s now becoming more common for myself and colleagues to support a child with TB, as a result of the conditions they’re living in. I think that’s probably the most damning illustration of the extent of the crisis we’re in, and the housing-mediated violence that’s inflicted on disempowered communities.

Health workers are burnt out. Directly and indirectly, the housing crisis is feeding into people leaving the profession, no doubt. Colleagues feel a deep-seated sense of helplessness and feel redundant in their capacity to make meaningful health improvements in the lives of patients. Coupled with the existing pressures of working in a system that’s under-resourced, this leads to apathy. Because you’re faced with problems that you’re not given the capabilities to address. Clinicians are given a fork, where a knife is really needed to cut through the problem. Yes, the NHS does need resourcing but if we’re serious about “an ounce of prevention’s worth a pound of cure”, then that needs to be translated into policy. And that involves radically rethinking our housing and energy system, towards serving public good, not private profit.

Increasing the availability of social homes at social rents for the community and measures to stabilise spiralling private rents are a starting point. Because when the bulk of your income is going on simply keeping a roof over your head – and the rest on sky-high energy bills to stay warm – there’s simply nothing left in the tank to feed your children nutritious food that’s essential for their healthy development, let alone the breadth of resources, support and care they need to thrive.

Older people

Older adults are another vulnerable group whose health is impacted disproportionately by the housing crisis. Our polling showed that:

- two thirds (66%) of health workers see older people with a mental health condition caused or worsened by their housing

- just under two thirds (65%) of health workers report seeing mobility issues (eg trips and falls) linked to housing

- close to two third (63%) see older people with respiratory or cardiovascular illnesses

- and 43% see neurological conditions in older people caused or worsened by poor housing.21

Tom – geriatric consultant:

Mobility issues are a major problem for older adults. Too often, people are living in accommodation that doesn’t suit their basic needs. The second biggest issue I see is the impact of the cost of living. People not having enough financial security to eat well and put the heating on. The crisis of cold homes is often a very hidden problem, as particularly older adults don’t always disclose what is going on for them. When I visit people in their homes, people turn on their heating because they know they’re about to have guests, but I can see from the state of their home that it is normally not heated. I often have patients coming in with five layers of clothing and need to peel back each layer before examining them in the hospital, because that is what they need to do to keep warm at home.

The World Health Organization recommends that all homes are heated to between 18 and 21 degrees. This should be the minimum benchmark for all of our homes, and this is what should be guiding government policy. This has been a very difficult winter in terms of influenza and its impact on older populations, and we know that cold and damp homes make this a much worse situation than it needs to be. The energy system is completely inadequate and not fit for purpose, especially for older adults.

Disabled people

Disabled people are also being harmed by the public health crisis in our homes at a disproportionate rate.

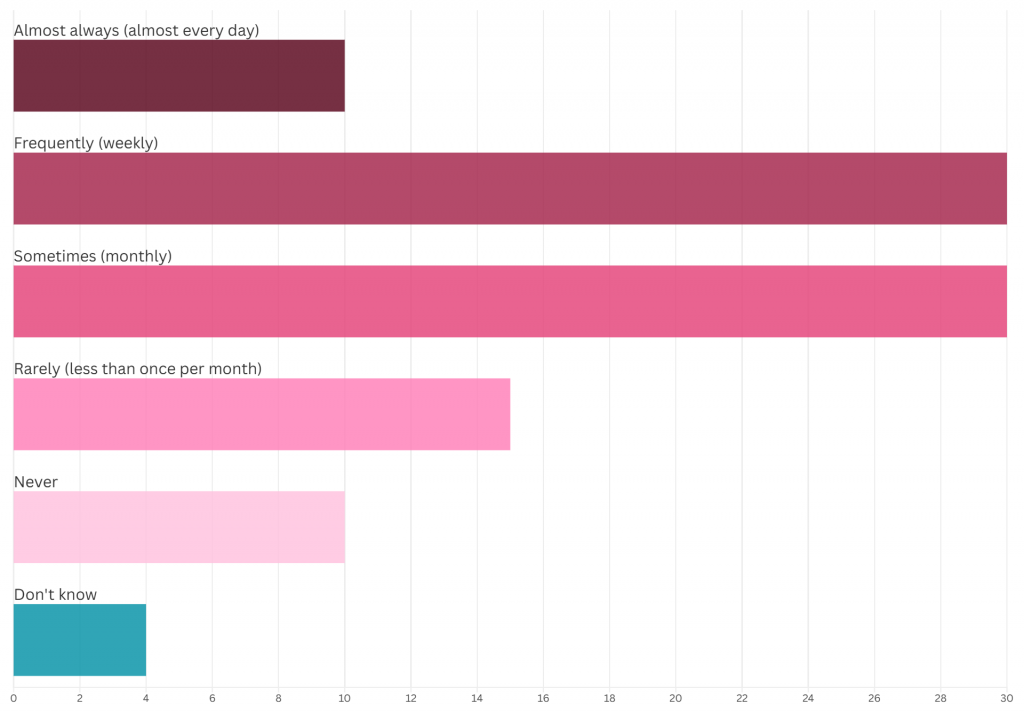

Our survey revealed that a shocking two thirds of health workers (66%) see disabled people who are living in unsuitable accommodation (eg unsafe or inaccessible housing) which is likely causing or worsening ill health regularly, ie at least once a month. As Figure 4 shows, of these:

- close to a third (29%) see disabled people in this situation monthly

- over a quarter (27%) see them weekly

- and a stark one in ten (10%) health workers see disabled people living in unsuitable accommodation almost every day.

Meanwhile, fewer than one in five (17%) said they see disabled people whose housing is likely harming their health “rarely” (ie less than once per month), and just 13% reported never seeing this.22

4. Costs of living

Against the backdrop of the wider cost-of-living crisis which has seen everyday expenses like fuel and food hit sky-high prices, the unaffordability of costs associated with housing – in particular, rent and energy bills – contributes hugely to poor health. Poverty entrenches health inequalities in myriad ways, such as through nutrition (as case studies here highlight), but also education, employment, income, and of course access to decent, warm, healthy homes – or lack thereof.

Unaffordable rents

Our findings showed that nearly two thirds (63%) of health workers have seen patients who describe expensive rent as an issue. In addition, over half (52%) have seen patients under threat of, or subject to, eviction or homelessness, a consequence which can follow from falling into rent arrears.23

Unaffordable rent has knock-on effects on people’s health, housing and wider financial situations, leaving many unable to eat properly or to heat their homes adequately, as explored below. As a result, more than half (54%) of health workers believe that high rents worsen chronic health conditions or delay treatment,24 and almost two in five (39%) believe unaffordable housing contributes to avoidable hospital admissions or contact with health services.25

Health workers see this state of affairs as preventable, however. When asked about policy solutions, more than two thirds (69%) said making renting more affordable would reduce the impact on the NHS. A smaller, but still significant proportion (58%) said increasing social housing supply – generally much more affordable than private renting – would reduce strain on the NHS.26

Yusuf – GP:

I’m working in an area with a lot of inequality. So you have a rich part of town and a poor part of town, and you can tell instantly the difference, it’s quite stark. On top of the obvious stuff about how damp can cause mould, or living in a cold home can cause respiratory conditions, and how living in overcrowded housing can impact your health, there’s also the indirect stuff you wouldn’t necessarily associate with bad housing. So, for example, I might have two different patients managing type 2 diabetes. One of them gets a blood test every three months, knows exactly what treatments they’re on, and they come through your door and within a minute or two you’ve managed to do what you need to do together. Whereas the other person hasn’t had a blood test in six or seven years, doesn’t really know what medications they’re on, or when and how to take them, and when they come in, the first five minutes are just trying to figure out what’s even going on. And obviously in a time-pressured environment, you try, but you’re not going to do as good a job.

If you’re in poverty, housing insecurity, or in overcrowded housing for years, all the other stuff that’s not even directly linked to that builds up. And then, next thing you know, your notes are a mess. No one knows what’s going on with you. And then all these different things that should be quite simple, and you should be in and out in two minutes, just become more difficult. And it adds up because if you’ve got diabetes, or you’ve got high blood pressure – very simple, easy conditions to treat – but you don’t have the capacity to get these things checked out on a regular basis, you’re the person in ten years’ time who’s much more likely to have a major complication, like diabetic eye disease, or a heart attack, or a stroke. It’s not the person that can check in with their doctor every three months because they’re in stable, secure housing. As a GP, you can’t fix the housing crisis in your practice. You’re just papering over the cracks.

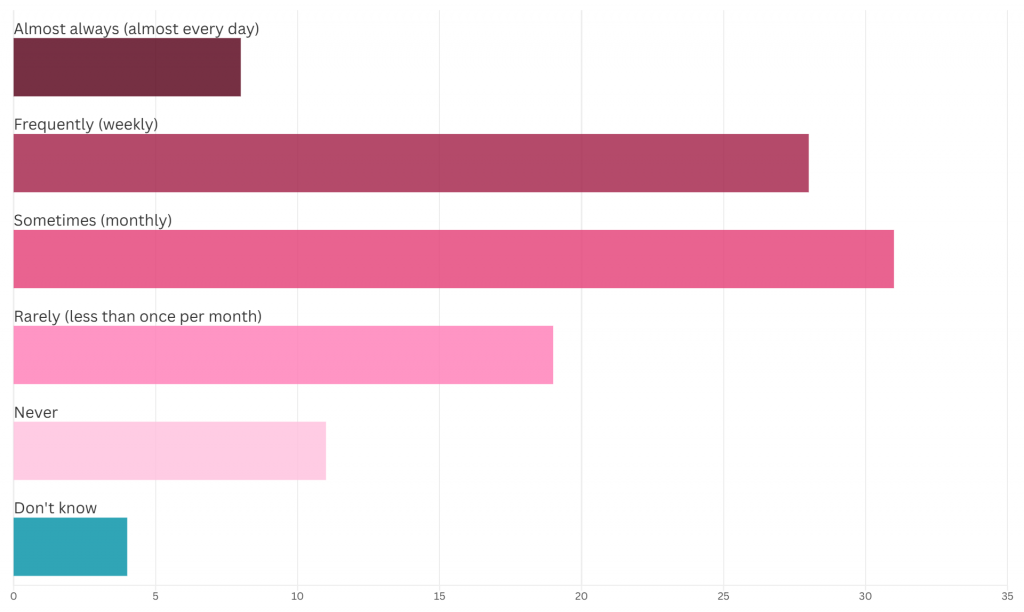

Cold homes and fuel poverty

In total, 65% of health workers witness patients living in excessively cold homes.27 Usually, cold homes are a direct result of being unable to pay the energy costs of heating. As Figure 5 shows, our survey revealed that more than two thirds of health workers (70%) regularly see patients forced to go without energy (eg heating) because they are unable to pay their bills. Of these:

- close to a third (30%) said they saw people in this situation monthly

- close to a third (30%) said they saw it weekly

- and one in ten (10%) health workers said they saw people in this position almost every day.

Only 15% said they saw patients for whom energy affordability was “rarely” an issue (ie less than once per month), and only one in ten (10%) said they never see patients struggling to afford energy bills.28

As a result, close to a third (59%) of health workers believe that high energy prices worsen chronic health conditions or delay treatment. A similar proportion (63%) said the same about poorly-insulated houses, another dimension of high energy bills and cold homes.29 An even greater proportion (68%) believe that high energy bills contribute to avoidable hospital admissions or contact with health services, with only 10% disagreeing.30

Yet health workers believe that measures could be put in place to alleviate the burden on the NHS, as well as on ordinary people. When asked about policy solutions, just over two thirds (67%) said improving energy affordability would reduce the impact on the NHS. A slightly smaller proportion (59%) said the same about policies improving energy efficiency in homes.31

Emily – psychiatrist:

When I worked in perinatal services, I saw a lot of women with babies who were living in unsuitable houses – cold, damp homes, temporary housing, shared homes with strangers. It was a really vulnerable time of their lives, and also a really critical time of that child’s life. I remember one woman I was treating who was in temporary housing with a lot of problems. It was really contributing to her severe depression and that was impacting her ability to bond with her baby. The baby was showing a lot of signs of emotional neglect, and that’s gonna shape the child’s life, those early experiences. Another time, we got a call one night in winter from one of our service users because she was being evicted with no warning and didn’t have anywhere to go with her baby.

I also met a teenage boy who felt too self-conscious to play sports wearing shorts anymore because he had really bad excoriations on his arms and legs from eczema, which was caused by the damp in his home. His GP had written to the council numerous times but the family had not been rehoused. I can also think of a number of people living in homes which are completely unheated and dangerously cold, because of their finances – maybe even been cut off by their supplier. It’s a huge burden on them, and on the NHS too. People are more vulnerable to viral and respiratory illnesses and sometimes they’re pushed into mental health crises by their housing situation, because of the additional stress in their lives, on top of financial worries, and work stress. It’s not just patients, by the way. The last three homes I’ve lived in – all rentals – had slugs coming in every night, they were that damp!

5. Effects on health workers and the NHS

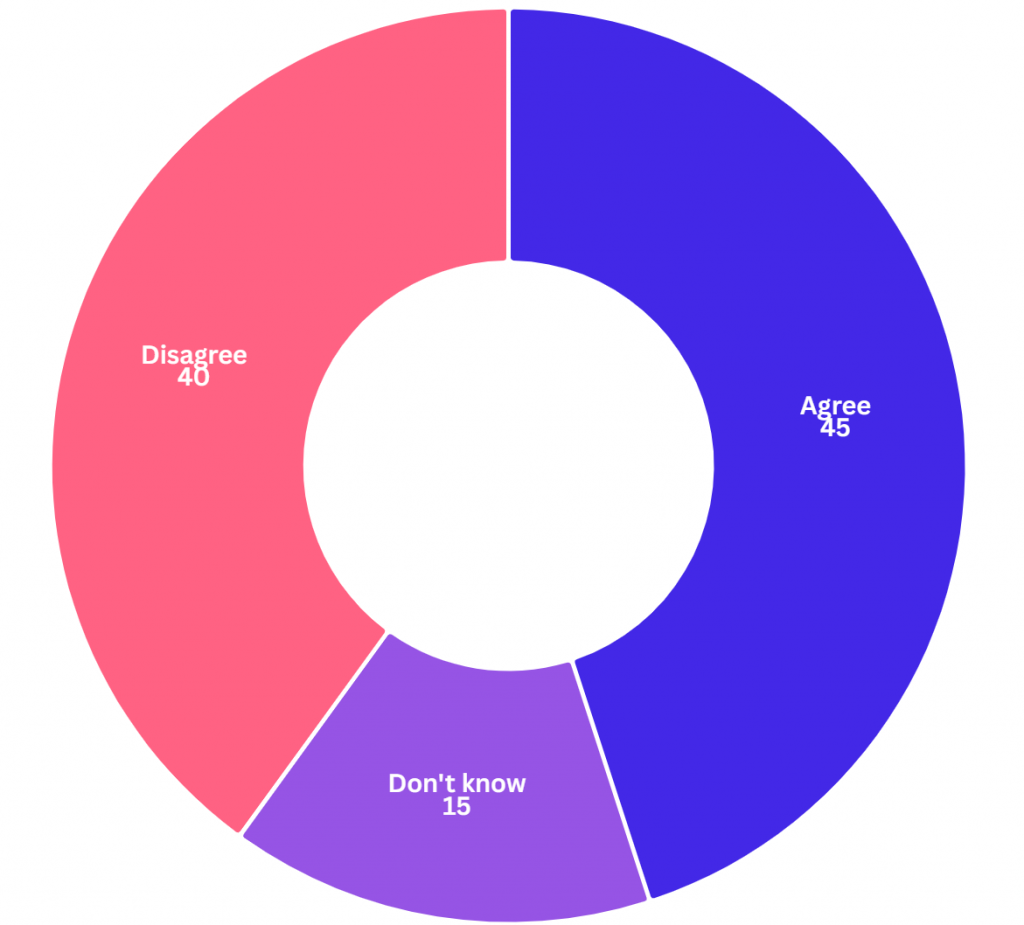

Given the systemic nature of the housing crisis, more than two thirds (69%) of health workers agreed with the statement “I feel powerless to support my patients with their housing conditions”.32 As Figure 6 shows, almost half (45%) of health workers have had to send a patient home knowing that their housing situation would make them ill again.33

The moral injury caused to individual health workers by this status quo, and the effects on collective worker morale, also evidenced by the qualitative testimonies in this report, should not be understated. The knock-on effect on staff retention also contributes to the cumulative strain on the NHS. As the introduction noted, prior research has found that poor housing costs the NHS an estimated £1.4 billion every year.

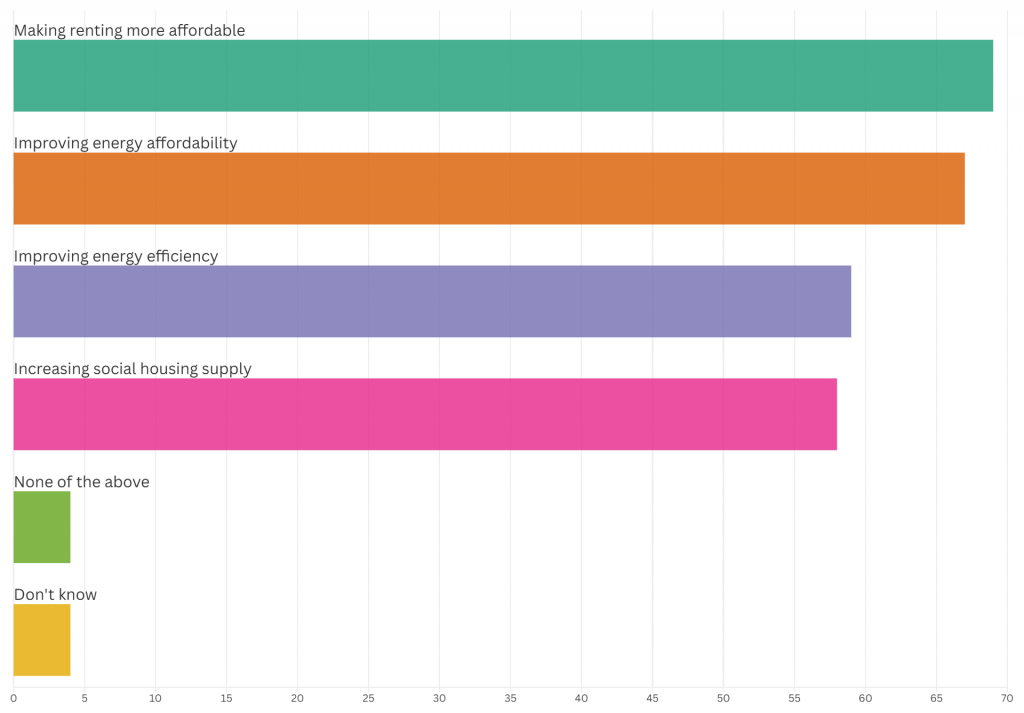

Health workers know that prevention is better than cure. More than two thirds (69%) saw upstream policies addressing the public health crisis in our homes as superior to the NHS treating the symptoms later down the line, and agreed with the statement “government spending to prevent illnesses created by cold homes is better for the NHS than having to spend money to nurse patients back to health”.34 As Figure 7 shows, asked about which specific policies they believed would reduce impact on the NHS:

- more than two thirds (69%) said making renting more affordable

- just over two thirds (67%) said improving energy affordability

- a significant majority (59%) said the same about policies improving energy efficiency in homes35

- and a slightly smaller proportion (58%) said increasing social housing supply.

Finally, it should be noted that the housing crisis is not only showing up in health workers’ lives via the patients they treat. Many health workers were themselves affected by housing issues. More than two in five (41%) said their mental health had been affected and almost a quarter (23%) said housing issues had impacted their physical health.36

Laura – respiratory doctor:

Quite often people will get their phones out and show me the black mould that they’re living with. People say: “I’ve tried, and I’ve tried, and I’ve tried, and I’m not getting anywhere. The maximum they will do is come round, just paint over it.” And these are patients who are living with chronic lung disease, coming back to the clinic again and again. I’ve started documenting diagnoses like: “This is breathlessness, ongoing cough, chest infections, inflammation in the lungs. Asthma, bronchiectasis, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) – caused and exacerbated by damp and mould in the home”.

Another patient with chronic lung disease was pregnant and living with her husband and son in temporary accommodation – a single hotel room on the 11th floor of a building where they are replacing the cladding. So they were exposed to dust from the work. She has relatives who died in Grenfell, so all of this is incredibly triggering. She has had to go in person, with her chronic lung disease, and pregnant, to the town hall, to advocate for herself and her family to be rehoused. Then the council tried to evict her when she was 38-weeks pregnant, and rehouse her into a mouldy, damp basement flat. You just couldn’t make it up!

Another patient I saw had been diagnosed with asthma at 40 after she had developed a chronic cough. I wondered why she had developed it as an adult, so I asked about her housing and her daughter – who was translating – said, “her house is so mouldy, I don’t take my baby daughter round there, it would be dangerous.” So they knew why she had asthma – but it wasn’t in any of the medical records. Nobody else had asked about her housing. It’s almost like it’s an invisible problem, a hidden problem. Even when patients are identifying it, or bringing it up, doctors don’t really get involved. Why would you get into a conversation about housing when you know there’s no chance you’re going to be able to help this person?

There’s this rhetoric that there isn’t enough housing. And maybe that’s true, there certainly isn’t enough suitable housing, but there are empty houses. And there’s housing that could be better if there was money for proper repairs. The reason we’re in this mess is that people are buying up places to make money. But a home’s not something that should be bought and sold for profit.

6. Conclusions

Millions of people in modern Britain do not have access to the secure, accessible, affordable, warm and good-quality homes they need as a foundation for a safe and happy life. Instead, they are trapped in dangerous, unaffordable, overcrowded, cold and unstable homes. This is causing a public health crisis showing up not only in patients’ minds, bodies and communities, but also affecting health workers and the NHS system as a whole.

It is clear that the public health crisis in our homes harms some groups more than others, entrenching health inequalities and intergenerational injustice along lines of race, class and disability, and particularly hurting older people and children. The tragic and preventable death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak in Manchester, from breathing issues caused by black mould about which his father had repeatedly complained to the council, and the social murder of 72 people in Grenfell Tower, west London, are stark reminders of the consequences of the government’s neglect of its duty to provide safe, healthy homes.

However, this status quo is not inevitable and it can be changed. Regardless of who we are, the solutions all of us need are the same. But the solutions cannot be implemented by health workers in the clinic. The causes – and the cures – are social, political and economic. The policies summarised in the recommendations below (outlined in more depth in previous Medact briefings) represent a powerful opportunity to meaningfully address key sources of illness in the UK. Across Britain, health workers are organising alongside tenants to make these changes reality.

7. Recommendations

Recommendations to the UK government:

- Build good-quality social housing and repurpose private rented homes to create a new generation of social homes, so that everyone has a place to call home.

- Reform the right to buy to fix the chronic shortage of affordable social housing.

- Start a mass retrofitting programme to properly insulate and ventilate all homes (social and private rented).

- Implement the Decent Homes Standard & Awaab’s Law across the private rented sector as promised, ensuring robust processes for accountability if they are not met.

- Implement rent controls to prevent extortionate exploitation by greedy landlords.

- Abolish Section 21 eviction orders, as promised, to give tenants more security.

- Roll out a social energy tariff for people struggling to pay bills.

- Create a national energy guarantee so that everyone can afford to heat their homes.

- Bring our energy network back under public control so it serves the common good, not private interests.

- Embark on a rapid just transition, investing in renewable energy to ensure access to cheap, clean energy for all.

Notes and references

- Rahil Sheikh, ‘“Billionaires own my mouldy rental property”’, BBC News, 10 February 2025, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c0rq2g0kz1lo.

- Mustafa Javid Qadri, ‘Nine million spent Christmas in “Dickensian” housing conditions, survey finds’, Independent, 29 November 2022, available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/christmas-cold-electricity-heating-bill-b2252577.html.

- Michael Marmot et al. (2020), Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On, Institute of Health Equity; ‘What is the Housing Emergency’, Shelter, n.d., available at: https://england.shelter.org.uk/support_us/campaigns/what_is_the_housing_emergency.

- Helen Garrett et al. (2021), The cost of poor housing in England, Building Research Establishment, available at: https://files.bregroup.com/research/BRE_Report_the_cost_of_poor_housing_2021.pdf.

- Emma Hock et al. (2023), ‘Exploring the impact of housing insecurity on the health and well-being of children and young people: a systematic review’, Public Health Research 11(13), available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK598817; Shelter, (2006), Chance of a Lifetime: The impact of bad housing on children’s lives, available at: https://assets.ctfassets.net/6sxvmndnpn0s/4LTXp3mya7IigRmNG8x9KK/6922b5a4c6ea756ea94da71ebdc001a5/Chance_of_a_Lifetime.pdf; The Childhood Trust, (2021), Bedrooms of London: The context to London’s Housing crisis and its impact on children, available at: https://www.childhoodtrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bedrooms-Of-London-Report-1.pdf; Penny Bernstock et al., (2024), The Impact of inadequate housing on educational experience: A Pilot study in Newham, Citizens East London, available at: https://citizensuk.contentfiles.net/media/documents/CITIZENS_-_The_Impact_of_inadequate_housing_on_educational_experience_v4.pdf.

- Barnes, C. et al., (2024), “The Public Health Case for Social Housing”, Medact, available at: https://www.medact.org/2024/resources/homes-for-health-the-public-health-case-for-social-housing/.

- Carvalho, M., et al., (2004), “The Public Health Case to Warm Our Homes, Not Our Planet”, Medact, available at: https://www.medact.org/2024/resources/homes-for-health-the-public-health-case-to-warm-our-homes-not-our-planet/.

- For questions focused on the health of children and the health of older people, the sample was limited to those health workers who interact with these populations, giving sample sizes of 1,157 and 1,497 respectively.

- Survation, (2025), Survey of Healthcare Workers: Analysed by Survation on behalf of Medact, available at: https://stat.medact.org/wp-uploads/2025/04/Survation-Survey-of-Healthcare-Workers-for-Medact-2025.pdf.

- ‘Regularly’ here means at least once a month and is an aggregate of ‘almost daily’, ‘weekly’ and ‘monthly’ responses.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q2.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q14.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q3.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q1.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q5.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q4.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q9.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q7.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q8.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q10.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q11.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q12.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q1.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q5.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q13.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q16.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q1.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q6.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q5.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q13. The remainder either selected ‘neither agree nor disagree’ or ‘don’t know’.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q16.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q13.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q14.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q13.

- Survation, Survey of Healthcare Workers (2025), Q16.